How does one “see” a poem? Is seeing a poem like reading a painting, a friendly metaphor that brings together various perspectives on literature and art? As such, are there any poems that can not be seen, apart from those that commit the unforgivable sin of speaking in abstractions? If not, can the metaphor succeed in capturing a particular set of texts, rather than the genre in its entirety?

Paul Manfredi’s Modern Poetry in China: A Visual-Verbal Dynamic revolves around what the author calls a visual dimension in modern Chinese poetry. This has three components: (1) imagery, (2) references to seeing, and (3) the visual materiality of the text. The third component is foregrounded in mixed-media work that combines poetry with non-script visual material such as painting and drawing. In the Chinese context, it also refers to calligraphy, and to the physical shape of Chinese characters at large. The second component is the least prominent in the analysis. Perhaps this is because “seeing” poetry does not necessarily have greater impact if what the reader sees includes agents in the text who are in the act, or the experience, of seeing whatever it is they see. The first component, imagery, is the one that begs the questions asked in the opening paragraph of this review. And another: isn’t imagery inherently visual to begin with?

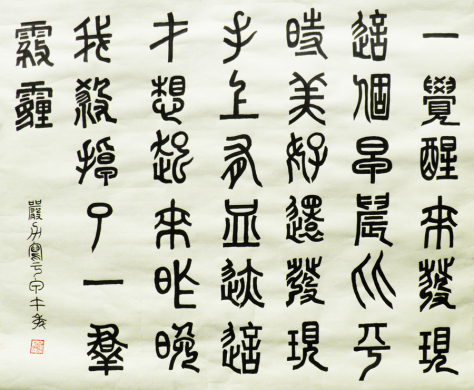

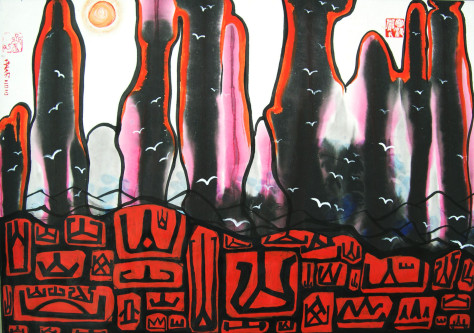

While Manfredi (wisely) doesn’t argue that visuality-through-imagery is any more salient in Chinese poetry than in poetries in other languages, he establishes interesting connections between the visual and the verbal in the Chinese context, in various individuals, historical settings, and media. In fact, there is a fourth component in addition to the three he identifies, in his use of the individual author as an organizing principle, since the poets whose work he studies have “pure” (i.e. non-script) visual artworks to their name that interact with their poetry in various ways. Obviously, such interaction can extend to the reader/viewer’s expectations and assumptions. A visual take on an individual poetic oeuvre may well be encouraged if one knows that the poet in question is also a visual artist. Reproductions of paintings—and in one case, of a sculpture—are included at the end of each of the chapters that make up the body of the book, along with visual material that draws on the Chinese script. The latter includes more or less conventional and highly unconventional calligraphy, seals/stamps, and literally cut-and-pasted collage.

The introduction is followed by chapter-length case studies on Li Jinfa, Ji Xian, Luo Qing, Xia Yu, and Yan Li. In the introduction, Manfredi calls Li Jinfa and Ji Xian representatives of “an early stage in the development of modern Chinese poetry”—although 1920s China is a different place from 1950s or 1960s Taiwan—and Luo Qing and Xia Yu, representatives of “contemporary poetry-visual art overlap in Taiwan (and beyond).” He describes Yan Li’s work as “a bridge across numerous geographical and temporal spheres—drawing the experimental era of the 1970s in China together with the twenty-first-century poetry scene” (p. xvi). Notably, this description would work equally well for Luo Qing and Xia Yu. Other verbalizers-cum-visualizers including Mang Ke, Ouyang Jianghe, Che Qianzi, Lü De’an, and Sun Lei make briefer appearances, in a final chapter on what Manfredi calls visual-verbal convergence in present-day China that is followed by a brief conclusion.

Especially in the introduction and in chapters 1 and 2, on Li Jinfa (1900-1976) and Ji Xian (b. 1913), Manfredi presents modern Chinese poetry and the modern Chinese lyrical subject as emerging into a fundamental instability, occasioned by the violence of the encounter with foreign modernity and the rupture with the indigenous tradition. In the process, he never succumbs to simple equations of Chinese with traditional, and foreign/Western with modern. This is illustrated by his attention to the resonance of Tang poet Li He in Li Jinfa’s work, and to Ji Xian’s concept of horizontal transplantation, and it is reinforced in later chapters by his discussion of Luo Qing’s, Xia Yu’s, and Yan Li’s international presence. In each case, this presence is deeply personal, and impossible to pigeonhole in simple terms of origin, influence, linear development, or definitive belonging—i.e., of who was (w)here first, and who gets (t)here next.

More generally, Manfredi reaffirms the problematic nature of easy dichotomies of Chinese + tradition and foreign/Western + modernity, by localizing his engagement with the notions of modernism and a modernist aesthetic, with the occasional reference to Bhabha and Appadurai. Focusing on the radical change that modernism brought to the reading/viewing experience as much as to the material itself—inasmuch as the two can be disentangled—Manfredi gives pride of place to (visual) self-portraiture, especially in the chapters on Li Jinfa and Ji Xian. This is a good move, in light of the turbulent life and times of the modern (Chinese) lyrical subject, and the identity crisis that has become a paradoxically productive feature of modern (Chinese) poethood.

In Chapter 3, on Luo Qing (b. 1948), Manfredi highlights the idea of Luo as a modern literatus (文人) whose work conjoins and blends (Western) modernist techniques and aspects of traditional Chinese literati culture. One key point in this respect is Luo’s engagement with poetry and calligraphy and painting. This is often manifested syncretically, within the space of one and the same work of art, including the use of traditional personal seals, albeit in decidedly new forms. Another key point is Luo’s involvement in a kind of theoretical reflection that is seamlessly part of a greater discursive whole also encompassing creative writing—even if the academic setting from which Luo operates is a different kind of institution than the government settings that were the habitat of the traditional literatus. Luo’s writings on his Shanghai-based School of Contingent Calligraphy (书法妙悟学派) are a case in point.

Manfredi acknowledges that the central position he assigns to modernism is rendered problematic by Luo’s work—which has convincingly been classified as postmodern—and, perhaps even more so, by Xia Yu’s (b. 1956), which is the subject of chapter 4. But if Luo and Xia are connected by postmodernism, there is rather more that sets them apart. For one thing, Xia Yu’s decades-long presence and explicit positioning on various cultural scenes in Taiwan and elsewhere is as anti-institutional and anti-classificatory as it gets. And of course, aside from their metatextual discourse, that Luo and Xia are fundamentally different poets is immediately clear from their creative work.

While Luo appears invested in creating some sort of order, even if this is often of the associative and playful kind, Xia does anything but create order, and her work subverts meaning itself, and language as a medium for meaning. Xia’s poetry is well known for its radical physical mediation and presentation, frequently leading to a degree of literal illegibility—transparent pages, semi-visible palimpsests—in addition to her considered disregard for the rules and conventions of syntax. Manfredi speaks of the “impenetrability” of Xia Yu’s work, and its resistance to interpretation-as-“penetration” (pp. 106-107). In light of his spirited engagement with her work, which definitely produces interpretations, it would have been interesting to learn more about his conceptualization of the interpretative process. If, for Xia Yu’s poetry, straightforward reading-for-meaning feels like banging one’s head against a wall, what are the moves we must have made when somehow, we find ourselves having read, and being no longer in the same place? Have we looked over our shoulder, turned outward, circumvented something, gone underground or taken flight, or learned to disintegrate or decenter ourselves?

Chapters 1 through 5 appear in the table of contents with their main titles only, with subtitles appearing on the first page of the actual text. The main titles of chapters 1 through 4 are simply the names of the poets in question: Li Jinfa, Ji Xian, Luo Qing, and Xia Yu. While chapter 5 is called “Phanopoetics” in the table of contents, the fact that the actual chapter text is subtitled “Yan Li and Poetic Re-vision, 1979” suggests that here, too, the individual author remains in place as the chapter’s organizing principle, even if Manfredi claims that looking through the prism of Yan Li’s (b. 1954) work enables us to see a larger trend emerging around this time. Perhaps this is why, different from the others, this chapter marshals a great deal of historical context, offering an extensive account of socio-political and cultural developments leading up to and into the reform era. As signaled by his above-mentioned description of Yan Li as a bridge across geographical and temporal spheres, Manfredi appears to see Yan’s work as somehow pulling together, or interconnecting, the visual-verbal dynamic of modern Chinese poetry. Or, he sees the mainland-Chinese historical moment of the late 1970s and the early to mid-1980s as doing so, with Yan Li as an exemplary painter-cum-poet.

What Manfredi sums up as the emergence of unofficial culture—including the Stars Painting Society (星星画会) and the literary journal Today (今天), both of which had Yan Li among their core contributors—was doubtless a crucial juncture in modern Chinese cultural history. Yet, it is difficult to see how this can assume a significance that is of a different order than that of, say, the New Culture Movement of the 1910s and the 1920s, or the decades-long, intensely transformative dynamics of cultural production and practice in Taiwan from the 1950s onward—or, for that matter, various moments in Hong Kong’s cultural history. Fleeting reference to historical background is made in chapters 1 through 4, and Manfredi notes the similarities between the New Culture Movement and the early reform era, but chapter 5 remains top-heavy in this respect.

Amid this plentiful historical context, Manfredi does offer valuable insights on Yan Li’s work, on which he is an expert. He shows Yan’s talent and originality in both painting and poetry, noting in particular Yan’s early ability to extract himself from the confines of what must have felt to many—poets and readers alike—like an irretrievably politicized discourse. Steering clear of the heavy and sometimes solemn tone of much early Misty/Obscure (朦胧) poetry, Yan was a trailblazer for a lighter tone, and for irony and humor. Over the years and the decades, following his mid-1980s relocation to New York, he has also played a notable role in internationalizing the poetry scene, especially through his editorship of the journal First Line (一行).

It is not clear, however, that phanopoetics is a suitable category for characterizing Yan Li’s work, or modern Chinese poetry in general. The term comes from Ezra Pound’s tripartite scheme of phanopoeia, melopoeia, and logopoeia, crudely rephraseable as (the making/emergence of) image, music, and “words”—but perhaps we should simply stick with logos here. If phanopoetics has to be central to the analysis, for Yan Li and/or other poets, this would require more theorizing of the issues surrounding imagery and visuality raised above, and the discussion would have to go beyond the case Manfredi makes for “seeing” poetry. For all its elegance and apparent simplicity—and with due acknowledgment of the energy of the materiality of the text—the metaphor sidesteps issues that are as complex as they are fascinating, and as intellectually charged as they are intuitive.

In chapter 6, in a discussion of (visual) works by Yan Li, Mang Ke, Ouyang Jianghe, Li Zhan’gang, Che Qianzi, and Sun Lei, Manfredi submits that in twenty-first-century China, the verbal and the visual are converging, not just conceptually but also in the organization of cultural scenes and settings. The argument is contextualized with reference to the changing landscape of cultural production, particularly places like the 798 former factory complex turned art space, in northeast Beijing. Manfredi claims that this is, to some extent, a return to traditional Chinese artistic practice, where the verbal and the visual were inextricably intertwined as different aspects of one and the same artistic moment. The nexus of poetry, calligraphy, and painting is the foremost example, even though in practice few individuals excelled in all three.

There is no ignoring the massive presence of indigenous traditions anywhere in cultural China—least of all in mainland China, where they have been making a gradual come-back since the 1980s, in the wake of May Fourth iconoclasm in the Republican era and virulent anti-traditionalism of another sort in the Mao era. Yet, if the convergence of the verbal and the visual is truly a trend, it is hard to see how this would be a return to cultural practices and identities that existed in, well, a different world from today’s. Rather, one might view it as the manifestation in one particular place of the well-known phenomenon of creative minds working in more than one medium. Painter-poets are not exclusive to cultural China, or to modern or traditional settings. At any rate, while Manfredi doesn’t claim we are witnessing The Return of the Literati or some such thing, he does posit a vital connection between the modern Chinese poet and the indigenous tradition, at some length in the introduction and in passing in later chapters. This is not altogether convincing, and one would perhaps expect a more balanced consideration of “horizontal” dynamics, on the one hand—i.e.inter-cultural or transcultural mobility and encounter across places, languages, cultures—and “vertical,” intra-cultural dynamics, on the other. If these things are inseparable, this does not make them indistinguishable.

What’s more, the way in which the argument on linkage with the tradition is put forward further complicates the discussion of visuality (and aurality) in poetry. From the introduction:

This visual self-fashioning in poetry is . . . a partial view of a larger subjectivity in the modern era . . . and by taking it as my focus I do not intend to diminish the importance of the aural in Chinese poetry, modern or other. In fact, it is precisely because the power of prosody in classical Chinese verse . . . is arguably one of the ear—the classical Chinese poem is one that is heard—that a rift emerges between a classical poetics of sound and a modern poetics of sight. The strategy of any would-be modern poet must be to divorce him or herself from the sound of the poem. (p. xxvii, italics added)

That sounds matters a great deal in classical Chinese poetry is indisputable. But especially in a context that highlights visual self-fashioning in the modern era, saying that “the classical Chinese poem is one that is heard” also runs the risk of implying that the visual experience, from the physical shape of the writing to the workings of the mind’s eye, matters less in poetry from earlier times—which can hardly be Manfredi’s intention. And then, in chapter 6, we read:

the concern for poets writing in the last decade of the twentieth century by and large was not the image but instead the sound of Chinese poetry. (p. 182, italics added)

There is, then, occasionally, the feeling that the argument is unfinished, and that the inconsistencies one is bound to encounter in the process of negotiating a complex topic could have been addressed more effectively. This does not detract from the intellectual courage and curiosity that move Manfredi to venture outside the monodisciplinary domain, the richness of his material and his command of it, or the conscionable presentation of a many-sided narrative and plenty of food for thought.

While the Cambria Press is to be commended for its Sinophone World Series, and copy-editing and technical production are a tricky business for which less and less time appears to be available, there are typos and other infelicities in this book that should be corrected. One also wonders whether, conversely, the publisher has been over-involved in determining the book’s title, so as to raise findability in search engines. Both in general terms and with reference to the subject matter at hand, there are good reasons to speak of modern Chinese poetry (as this review has therefore done throughout), and not to speak of modern poetry in China. If it really had to be “Modern Poetry in X,” then X should have read “China and Taiwan,” or “Cultural China”—or, at the very least, the book should have started by explaining what China is supposed to mean here.

These things will hopefully be remedied in a second print run and/or an e-book edition. It would definitely be worth it for what is, in all, a well-informed, insightful contribution to scholarship on modern Chinese poetry, and cultural production and practice at large.

Maghiel van Crevel

Leiden University