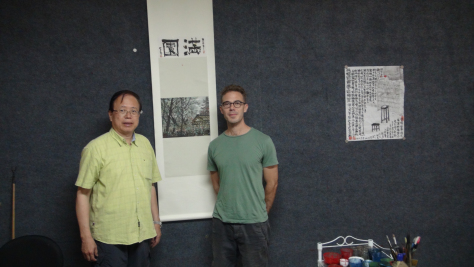

Last month at the American Comparative Literature Conference in Seattle, on a panel co-organized by Barrett Watten, Jonathan Stalling and Jacob Edmond, I was presenting on Zhong Biao. Here a brief digest of my remarks.

Title: Zhong Biao at the Margins of the Avant-garde

Highlights:

Broader context:

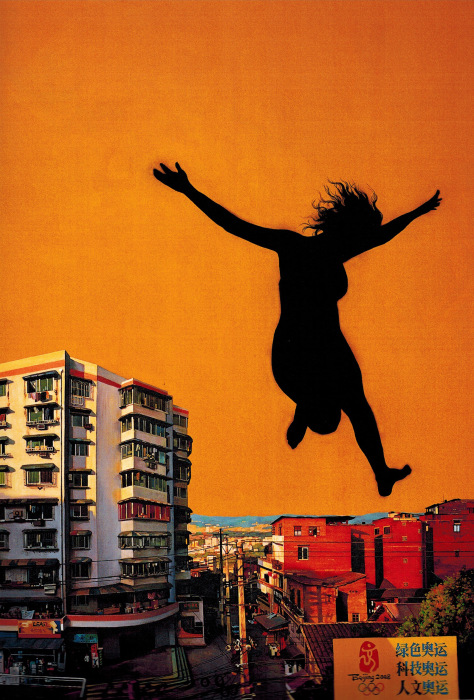

I am trying to situate Zhong Biao with regard to the contemporary Chinese avant-garde. In the process, I am posing the following question: if we begin with the assumption that essentially (and among other things) the avant-garde is a challenge to status quo, a compulsion to dissolve codifications wherever they occur (and particularly as they relate to or bolster ideological structures with mass influence, be they market appeal or state apparatus based on coercion), then what of a situation where so few codifications are in fact in effect? –that is contemporary China, a tear-it-up-and-rebuild-it ethos, be it in the array of material work of the built environment or in the circular waves of political campaign didactially deployed to lead the nation “forward” but, I suspect, more often than not not fooling anyone.

Zhong Biao focus:

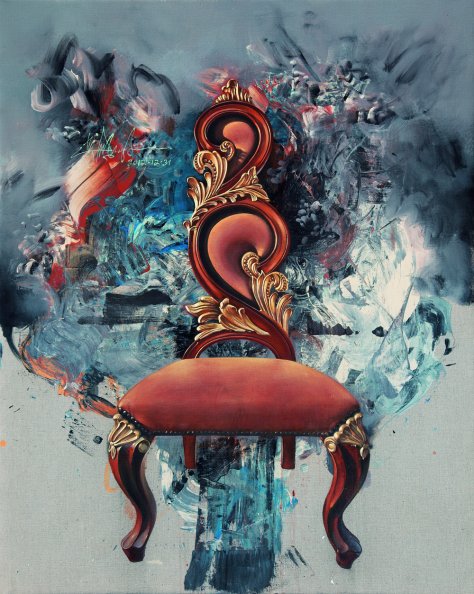

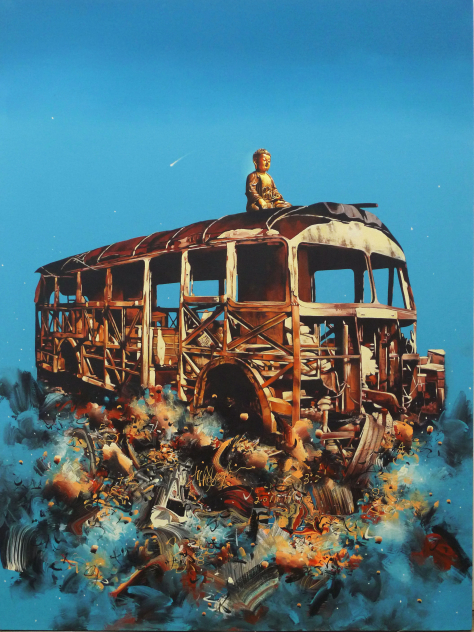

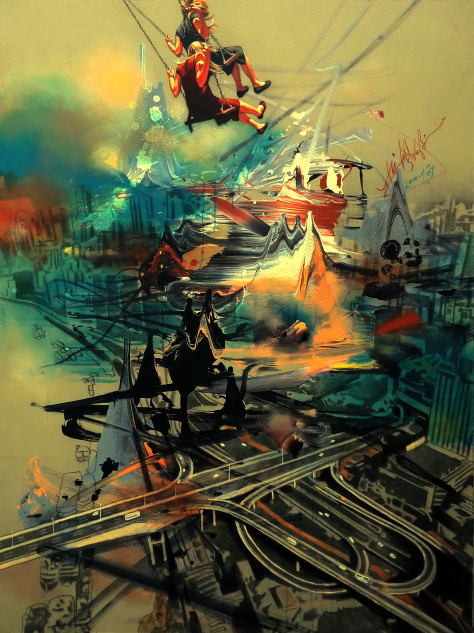

Zhong’s work strives, through a combination of abstraction and uncanny juxtaposition of realistically rendered figures from disparate space and time, to uncover latent energies or pneuma of the universe, manifest momentarily. The ephemera of our lives and ourselves emerge in his painting at the point of concretization but also dissolution, and always in some inherent interconnectedness.

This is an ambitious project because Zhong’s work does not fit easily within the avant-garde. Indeed, I suspect many would argue that his work belongs in an opposite category, if such a category exists. Where avant-garde practice is oppositional and in some respects destructive, Zhong’s is affirming, constructive, and mainstream. The reason I believe such a conversation is even warranted is that an attempt to situate ZB in AG context encourages fathoming of the limits of each. While discovering limitations of an artist poised too close to market impulses is unremarkable, observing the edge (blunt rather than cutting?) of the avant-garde as marginal overlap with the market is perhaps news.

Images discussed: