Back to work on poetry again after what seems a long foray into art-only (+ politics, I guess) topics. Of late, current writing concerns self-portraits in word and image, with an ancillary focus on the concrete poem. The latter is inspired by the work of Luo Qing 羅青 , a poet-painter from Taiwan who has also done extensive research on modern Chinese poetry and Chinese culture. In the course of exploring Luo’s work I was further introduced the the following 1965 “Self-Portrait” by Chinese concrete poetry pioneer Zhan Bing 詹冰(綠血球 Taipei: 笠, 1965)

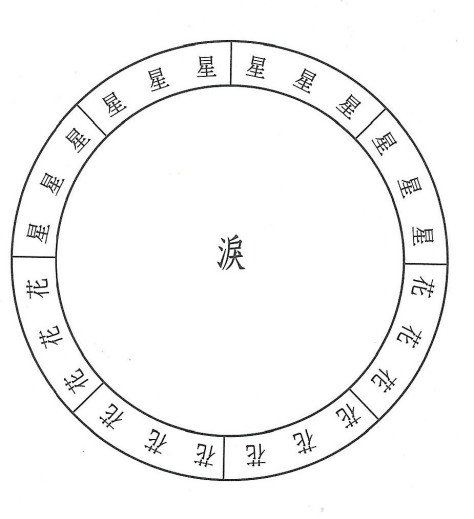

The image-poem is composed of three Chinese characters. The top xing 星 or star, the bottom hua 花 or flower, and the center lei 淚 or tear. The reading being something along the lines of : the revolution of the natural life cycle, from the universe-level life of stars to the locally observed course of single flowers, brings about a sadness in the lyrical subject, the “unchanging” center of ongoing impermanence.

Apart from what can be said about this intriguing work, I post it here only to complain about a strikingly contrasting reprint I’ve recently discovered. The new version appears in Zhan’s collected works (Taipei: Guoli Taiwan Wenxueguan, 2008) as such:

The difference between the two versions of this “same” poem is extraordinary. Whether or not the poet himself was involved in the selection of font or page layout is unknown to me (though I will endeavor to find out). Still, the former and presumably original version strikes me as more “accurate” in the graphic sense, which is to say that the look of the Chinese fonts, with the much larger and calligraphically arrayed “tear” is more intimate, vulnerable, and affective than the colder and far more angular reprint. There is also too much space surrounding the single tear. It could perhaps be argued that the second version reinforces the loneliness of human existence (space) and the remote nature of a relentlessly cyclical Nature (including emotional states such cycles give rise to), but I find these concepts already well-enough expressed in the first version.

Nonetheless, this concrete poem is a good case for meditation on the relationship between word-image-meaning. That some editor (or even the poet) thought this was the same poem strikes me as in and of itself worthy of note.