Visual artist poet and scholar Lo Ching (Luo Qing) has been now and again inclined to rework famous pieces of the Chinese tradition. In most cases, the “rework” has to do with visual interpretations of the literary tradition, itself much overlapping with visual. In some cases, though, Lo also rewrites the poems, taking one jueju 絕句 line at a time as the basis for his own new poetic line. In the following poem, the very well known “Deer Hermitage” 鹿 柴 by Wang Wei, Lo takes the final image of sunlight penetrating a deep forest and illuminating moss, and militarizes it. Wang Wei’s poem is in bold, and Lo’s lines follow beneath.

空山不見人

(Empty mountain, no one seen)

因為我是原始太初

Because I am the very first

第一個

Primeval animal

自覺為人的

To become suddenly aware of my

獸

Humanity

但聞人語響

(But human voices are heard)

因為我是大千世界

Because I am the last person

最後一個

In the whole wide world still able

還能獸語的

To speak

人

Animal talk

返景入深林

(Reflected light enters deep forest)

因為世上最後一線

Because the very last thread of the world

爆炸光閃

Explodes in a flash

射穿我空洞肋骨的

Penetrating deeply

深處 My bones and flesh

復照青苔上

(Again shinning on green moss)

因為整個黑暗的地球上

Because what remains of the dark world

只剩下一小塊彈片

Is but a bit of shrapnel, shimmering

在一層薄薄的青苔中

Upon the thinnest layer

明滅 Of moss

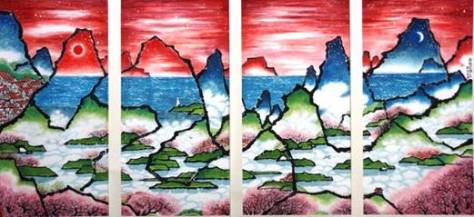

Among the many versions of visual performance of the opening lines of this poem (empty mountain, no one seen), the one below is my favorites:

I like this image in particular for the way that the word for person (人) appears in the word for mountain (山) –where, in terms of the characters themselves it does strictly “belong”– is a bit lost even so, drifting about the bottom of the word, slightly off kilter. The two characters at the right, in fact, have come apart from themselves more or less entirely, with the center of emptiness falling down on to the mountain, leaving two watery dots above.

In terms of self-referentiality, a feature notably most out of sync with the Chinese literary-art tradition, there is the obvious presence of Lo’s ink stamp, again not where it “should be,” appearing in the center of the painting. This bold demonstration of self is deftly mitigated, however, by the even more central location of the word NO () that separates the two characters of Luo Qing’s name, becoming something like “Lo NO Qing,” or “Qing NO Lo,” or simple graphic (non-sequential) demonstration of negation.