Yan Li’s poetry and art has been receiving a lot of attention of late in China. Among others, the online poetry portal New Poetry Canon 新诗经, started in 2012 by Gao Shixian, ran a lengthy piece (#067 May 15) containing many new poems. The opening introduction to Yan’s work also includes his recent work on the Autumn Moon festival, running annually in Beijing. That introduction as follows:

严力

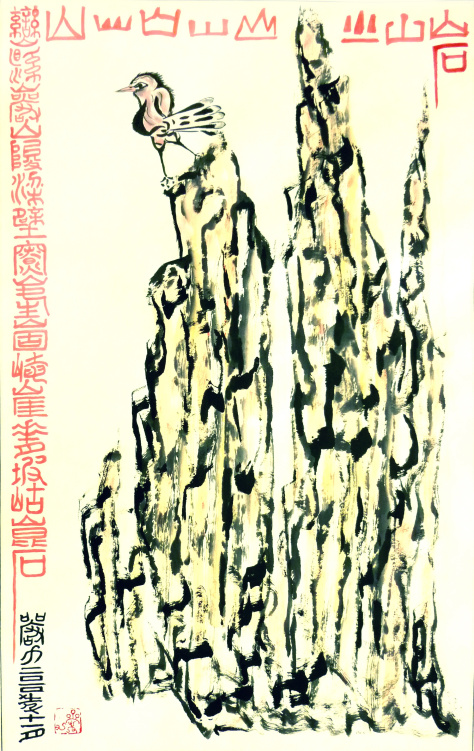

严力:(1954—)祖籍浙江宁海,出生于北京,旅美画家、纽约一行诗社社长、朦胧诗代表诗人之一。1973年开始诗歌创作,1979年开始绘画创作。是1979年北京先锋艺术团体“星星画会”和文学团体“今天”的成员。1984年在上海人民公园展览厅举办了国内最早的先锋艺术的个人画展。1985年从北京留学纽约并于1987年在纽约创立《一行》诗刊,任主编。2009开始主持每年一次的北京中华世纪坛中秋国际诗歌会。严力出版的有:诗集、中短篇小说集、长篇小说、散文集、画集等二十多本。画作被上海美术馆、日本福冈亚洲美术馆、以及私人收藏家收藏.作品被翻译成多种文字,目前定居上海、北京和纽约。

Yan Li: (1954-) native of Ninghai, was born in Beijing and has had long residences in New York, Shanghai and other cities. He began composing poetry in 1973, and in 1979 also joined both the avant-garde Stars artist and Today writers and artists collectives. In 1984 in Shanghai People’s Park Hall he held his first one-man show, in fact the first one-man show of avant-garde art in contemporary China. In 1985 he moved from Beijing to study in New York, and in New York in 1987 founded One Line. In 2009 he began hosting the annual Mid-Autumn Festival China Millennium Monument in Beijing international poetry meeting. Yan Li has published over 20 collections of poetry, short stories, novels, essays and other arts-related works. His paintings have been collected by Shanghai Art Museum, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, and private collectors. Works have been translated into many languages, currently we live in Shanghai, Beijing and New York.

Here, as well, the first poem, a short, 2-poem sequence, actually, with my translation:

门

1

对简单的形象

我一直很有亲近感

比如板凳和鞋拔子

唯有对门一直不敢轻信

主要是门后太复杂了

我还听说

为此有人在制作门的时候

特意往里面加进了敲门声

那是干什么用的呢

几十年过去了

我觉得真的很管用

门要时常敲敲自己的内心

DOOR

1.

I’ve always felt close to

Those simple shapes

Like benches or shoe-horns

Only doors I don’t approach lightly

Mostly for the complexity of what lies behind them

I’ve heard that

When doormakers make doors

They often have to add a couple of knocks inside

What can that be for?

After a few decades

I discover they’re really useful

Because doors too need to knock now and again

on the doors to their own hearts

2。

关在门里的门

是卧室的门

关在门外的门

是家的大门

而从来不用关的那扇门

还没诞生

The door in the door

Is the bedroom door

The door outside the door

Is the front door

And the door that never needs closing

Has yet to be born