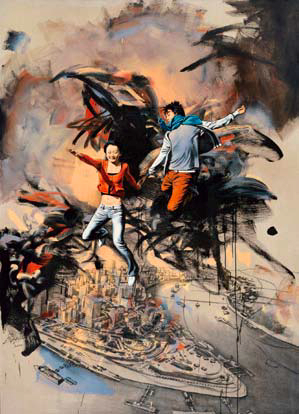

Liu Wei image from here

During Zhong Biao’s visit in December I found myself casting about for good questions to ask him. Once the “What are your influences?” “What materials?” “What process?” –type inquiries were all behind us, there seemed to be need for going deeper into how he views artistic practice, particularly in China. Never did I think that such an obvious question (posed not by myself, for what its worth) would be so productive in this sense: “what’s good?” I suppose I may have avoided such a question expecting Zhong to be difficult to pin down in terms of his likes and dislikes. True enough, dislikes are not the type of thing he’s inclined to discuss, and I saw no point in pressing the issue. What a surprise, then, when he effortlessly and emphatically took to the question of who paints well in China today. He said, without missing a beat, Liu Wei 刘炜.

The ensuing conversation brought to mind the criticism leveled against Zhong from a number of quarters (that I wont identify in this setting), namely that he is too market oriented. I’ve wrestled with this a bit, given that I would like to consider myself disinclined to interest in–much less promotion of–the blatantly commercial, and yet I’m fond of Zhong’s work. In this regard, Zhong’s remarks about Liu Wei brought to light an important difference in his mind at least between what he does and what Liu Wei does. Liu Wei is, according to Zhong Biao, purely a painter. Zhong Biao, meanwhile, is an artist. Liu Wei’s work is limited to the canvas, while Zhong’s extends out, to intercourse with the community, to performances of all kinds, to “projects” that are part installation, part promotion and finally part painting. Zhong Biao is constantly engaged in what’s next in terms of the showing, the scene, the event. What happens outside is at least as important as what happens on the canvas.

By contrast there is Liu Wei. His work begins and ends on the confines of the canvas. What happens there, though, and clearly what Zhong most appreciates, is the abandon, the transgression, the discovery of boundary, and the effortless, creative, and for Zhong even incredible disregard for the boundary. Liu’s work speaks to Zhong’s creative spirit, and does so in ways Zhong cannot.

I had been vaguely familar with Liu’s work already, having an impression of ruddy faces and ill-kept teeth. As I listened to Zhong, however, I realized that the artist is indeed extraordinary in his mercurial-ness: from those faces, which no doubt secured him some degree of audience, he moves to landscapes, and mixed-media. He moves, in fact, all about. And yet, as Zhong well observed, he remains on the canvas, where he belongs. A painter’s painter whose work I will now be following along with Zhong Biao.

from here