李洪涛

below is a short essay written as part of my work on abstraction in Chinese art and poetry

also in Chinese:

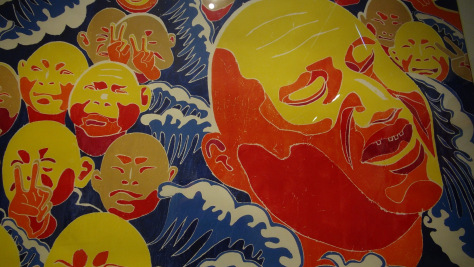

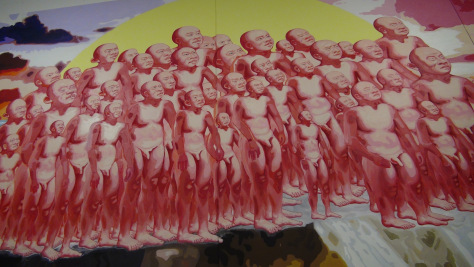

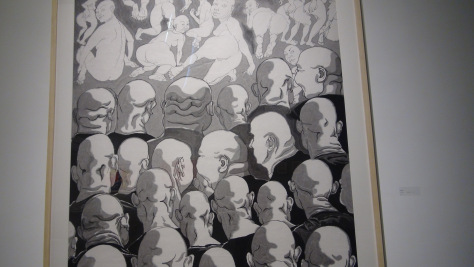

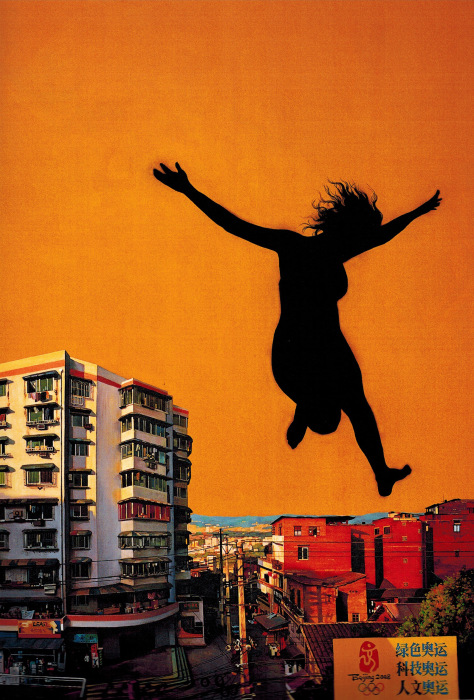

Abstract Healing of Li Hongtao

Li Hongtao was born in Dalian, China in 1947. He was not trained as an artist, having instead studied engineering, a career interrupted by personal tragedy–the loss of his father at a young age–and the collective catastrophe of the Cultural Revolution. After a brief engagement with culinary studies, Li took up visual art, a realm in which he is entirely self-taught. Nonetheless, in recent years he has established himself in major art networks, with solo exhibitions in Carlos Hall at the Louvre and the United Nations both in 2013, and numerous galleries and art institutions around the world.

Li’s paintings occasionally depict landscapes and other figures of usually natural rather than man-made origin, but by and large his work is done in a non-representational or abstract style. Though China certainly has a robust painting tradition stretching back centuries, and even a modern painting tradition based upon exogenous European examples from the 19th through 20th-centuries, the origins for abstract painting such as that produced by Li Hongtao are not in painting at all but in writing. This is because on a basic level the foundations of the Chinese writing system were at heart abstract, or better put, manifestations of “that which is of itself thus,” a paraphrase of the Chinese word “ziran” 自然 meaning nature. Chinese abstract art is by its very nature in line influential art critic Clement Greenberg’s view:

The avant-garde poet or artist tries in effect to imitate God by creating something valid solely on its own terms, in the way nature itself is valid, in the way a landscape–not its picture–is aesthetically valid; something given, increate, independent of meanings, similars or originals. Content is to be dissolved so completely into form that the work of art or literature cannot be reduced in whole or in part to anything not itself. (Art and Culture, Boston: Beacon, 1961: 6).

The Chinese writing system is derived, near as one can determine, from natural forms (li 理, or wenli 文理), patterns in bamboo leaves, landscapes, bird tracks or any other naturally occurring phenomena — all that is “aesthetically valid,” in Greenberg’s words, in and of itself. The hieroglyphic or pictographic stage followed from there, and the full Chinese character-based writing system soon after. Nonetheless, the abstract origin of all Chinese writing is ever-present for the calligrapher or artist to exploit, returning the word to the mere image, an object of contemplation in and of itself. Such was the case, for instance, in the work of Zhang Xu 张旭, Tang dynasty calligrapher who famously drank himself to a state of total inebriation and then produced wild, illegible but unanimously celebrated calligraphy. As a backdrop to abstract expression in China, there exists a rich array of examples from literature and art, a tradition which is, ironically, no less modern than anything produced in the West in the past two or three centuries.

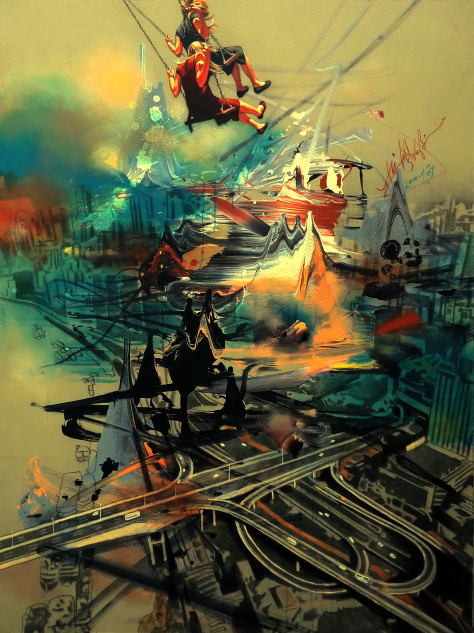

Beyond mere mentions of style, Li’s work is connected with traditional Chinese painting in uncommonly substantive ways. To begin with, he draws clearly from Chinese landscape traditions. Namely, his visual forms can be appreciated not simply for the two dimensional attributes of lines upon on the canvas, but instead for their three-dimensional penetration of the space through shading and intensity of color, again much the way calligraphy is at least as much about depth or degree of saturation of black and white as any given stroke or line. We don’t look at Li’s painting, we look into it. In so doing, though, we are engaged with the work in a fashion that is unlike regular artistic observation or appreciation. Li’s painting is a demonstration in traditional Chinese aesthetic terms not of a given “expression” of an artist, but indeed, of the artist himself, his person, even his moral or spiritual being, a form of the ancient Chinese adage that “writing is the delineation of the mind” 书心画也 (attributed to Yang Xiong 杨雄–53–18ce).

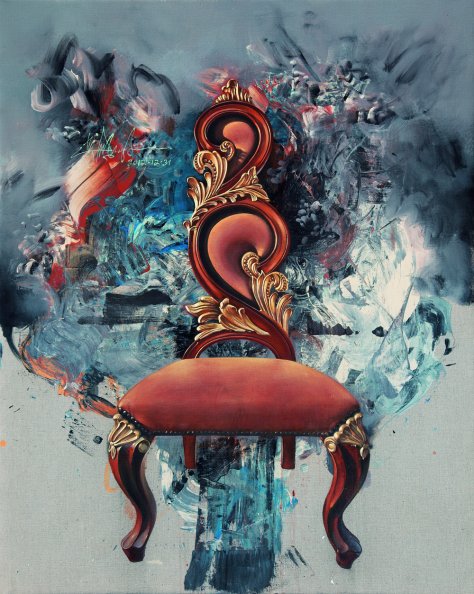

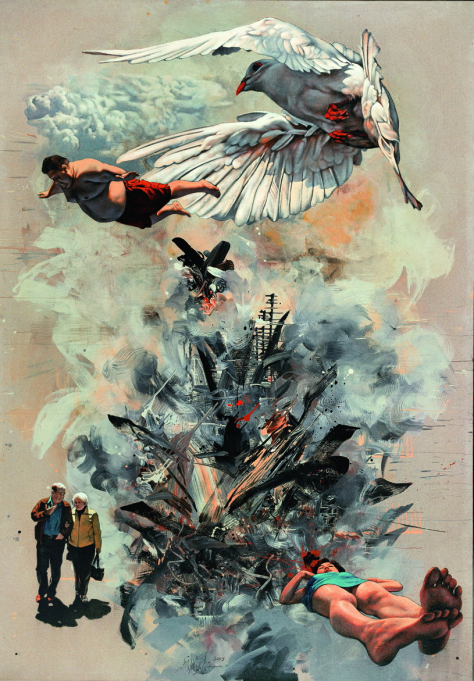

But Li’s work is alternatively known as “energy painting,” something which takes us deeper in to his work still, and where he transcends the East-West and perhaps even figurative-abstract divides altogether. With his particular ability to draw from the power of color, Li himself sees his work not only as something which pleases, or even challenges his viewers. His goals as an artist are even more ambitious that then. He takes the interaction with his paintings as a form of reclaiming essential balance, a kind of cosmic order which, rather than remote and spiritual, from the Chinese view of health and wellness is simply a function of the flow of energy through the universe. This flow pervades the five elements of the natural world just as it does the vital organs of the human body, a material realm enlivened by qi 气, a primordial power or energy which travels the meridians in the human body (along with all other living beings), flowing either freely or with obstruction depending on the degree of health in a given organism. The viewer’s interaction with Li’s painting activates and stimulates this flow, images that can be not only seen but actually felt in the viewer’s body.

Li Hongtao’s painting is the kind of aesthetic accord which demonstrates that fully individual, even iconic work can flow seemingly effortlessly from two sources at once– a rich and ancient aesthetic tradition in China, a more recent, assertive avant-garde practice in the West. However, while looking at Li’s work none of these origin stories really matter much. The painting speaks for itself, louder than words could ever manage.