As part of Zhong Biao’s visit, we organized a small panel discussion at Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle. Speaking were Zhong Biao and Jen Graves, visual arts editorial writer for Seattle paper The Stranger. I served as translator, as best I could.

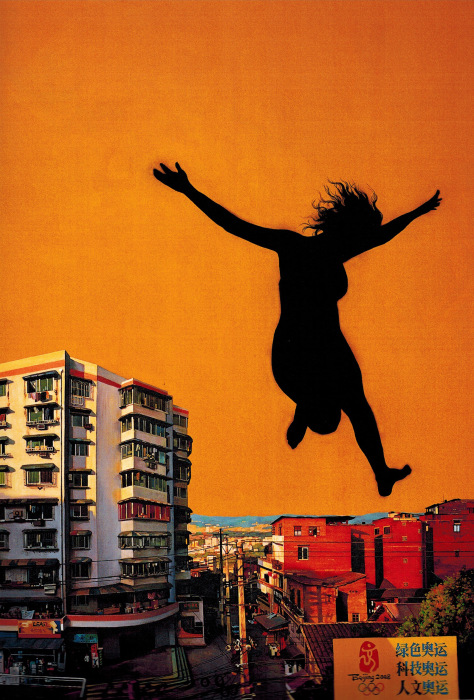

The event was very well attended, given the short notice, and the conversation wide ranging. Sooner or later (later, as it turns out), the topic almost inevitably turns to Ai Weiwei. I was pleased, though, to have the opportunity to mouth-piece an alternative view to the one that is frequently expressed in Western press. Zhong’s response to the Ai Weiwei question–if we might frame it simply as such–focused entirely on the idea of freedom. In Zhong’s view, an abstract “freedom” is not something we possess, or even “fight for,” and certainly not something handed to us like a trophy. Freedom is defined in contrast to (and therefore limited by) what constrains it. Like jumping up and down. One strives for the freedom that is above us, the clear sky. If, though, we were to actually get there, it becomes a very different story. The feeling of freedom we get with our leaping to higher elevation is actually provided by the force that pushes us down—gravity. Minus gravity, we’re just adrift. Ai Weiwei (in grass horse/fuck your mother images) can be seen leaping literally against this gravity. His power to do so figuratively, which in Ai’s case is all-important, is defined by the authoritarian gravity which he challenges day in and day out.

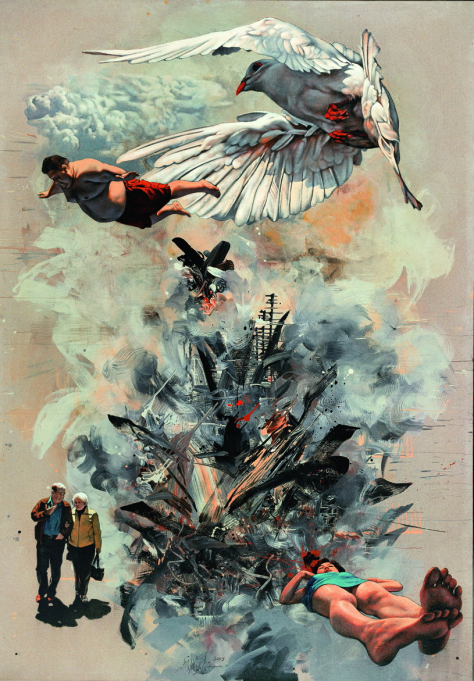

But back to Zhong’s comments. The discussion about freedom led abruptly to Zhong’s view about Chinese artists (and intellectuals) generally. In typically definitive fashion, he identifies two types of artist/intellectual: the destructive and constructive. Both types are necessary to advance artistic progress, which I might add seems to be taken by Zhong as essentially necessary. Ai Weiwei is an exemplar of the destructive type. Ai stakes out this position vis a vis existing power structures. Having clearly identified this target, he then endeavors to blow them up. If he does his work well–and it seems in Zhong’s estimate that he does–he can bring down the entire structure. Meantime, the other side working on building things up. These two are mutually dependent as one would be meaningless without the other.

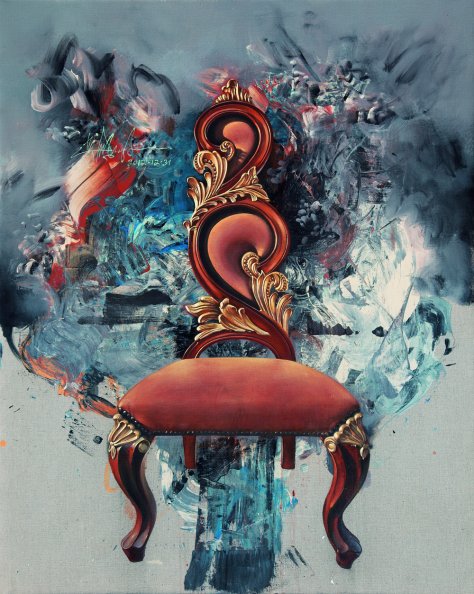

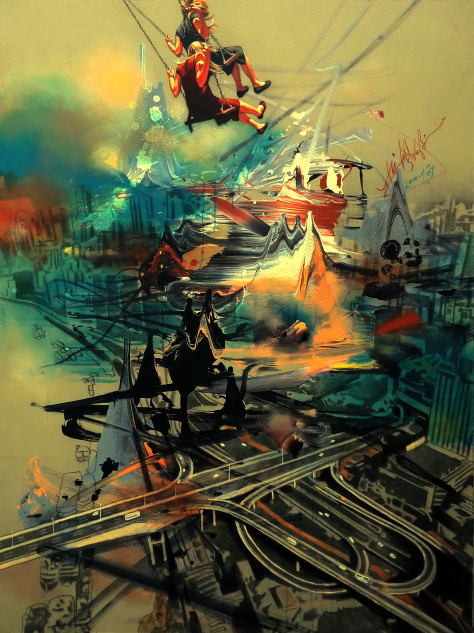

This dichotomy aside, Zhong and Ai strike me as having an interesting common element, namely the powerful consistency between what they believe and what they do as artists and as people. For both there is hardly any daylight between their lives as artists and as people, for lack of a better world. Ai’s case is well documented. Zhong, though, shares in this perhaps more than one would imagine. His photorealism, his abstraction, his symbols, and his opinions are all part of an integrated whole. Hence, while Ai Weiwei is challenging the limits of politically acceptable speech, Zhong is exploring gravities of other sorts.

…..