As promised in a previous post, a few words about the Ai Weiwei exhibit I happened upon while visiting 798 last month. Over the years, I have in various places and ways expressed reservations with Ai’s work, and more particularly, his reception in Western media. This exhibition, though, marks a kind of turning point in my appreciation of him, at least as an artist in China. I am reminded that he is in factstill full-voiced, relevant, powerful, and really worth the hype in many ways.

Ok, it seems important to mention that this is Ai’s first solo exhibition in China since he was censored all that many years ago (since 2008, to be precise). This is important because, in the political history which will come to dominate understandings of Ai in the coming years, Ai’s “return” to the Chinese domestic art scene signals either an escalation in the sometimes downright hostile tit for tat between artist and political authority, or perhaps a mollifying pivot to a kinder, more gentler relationship between Ai and his minders. I actually hope for the latter, if only because it has the greater potential to bring to view the type of work currently on exhibit at Gallerie Continua and Tang Contemporary Art Center.

For those not already aware, the exhibition is a reconstruction of an ancient (400-year old) dwelling located in Jiangxi that was slated for demolition by Chinese authorities. Here’s what it looked like from a photograph displayed in the exhibition:

Instead of such a fate, Ai has had a portion of the structure disassembled and then reassembled in two spaces, which are adjacently situated Beijing’s 798 arts district. I toured the exhibit, albeit too quickly, in the company of Sichuan artist Zhong Biao, whose impressions were in and of themselves interesting to record. What follows, though, is largely my take.

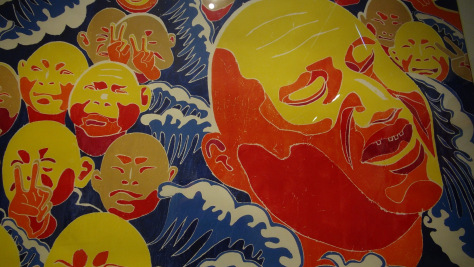

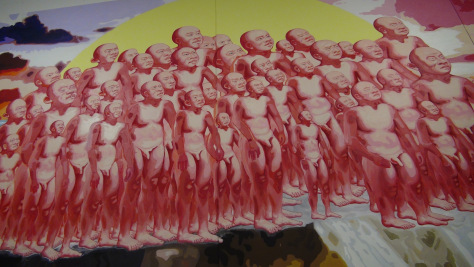

The colors.

The work is mammoth and impressive for sheer size and scale (and complexity). I’ll begin, though, with a small observation: the way that Ai paints some material objects found on site in the village in Jiangxi. We’ve seen this strategy many times in Ai’s work, most famously the ancient urns and other vessels which he similarly painted, and in some cases branded with marks of global capitalism (Coca-cola, for instance). The idea was clear enough to me in the past, and as an abstract notion — that crude paint on old and therefore venerated objects brings about meditation on value of all material objects in our midst — it made sense enough. But seeing is believing in this case. Here I am reduced to my own poor photography, which is not enough to convey just how vapid, yet vibrant, and saccharine to the point of being painful these colors really are.

The objects are painted ornamental elements of the original structure, brought to our view in a dedicated space of the gallery again as if to pose the question of viewing itself, ornamentation emanating from ornaments defiled and in their defilement emanating yet again. The effect is riveting, something like a car accident one views from the vantage point of a passing car. I both couldn’t bear to look, and couldn’t pull myself away.

The footings.

The colored objects (and also ladder, which I won’t get into here) are truly but a minor element in the vast work that, and here’s the major point, encompasses two full galleries. This is an important point because few artists in China living today could not only lock up two galleries for the purpose of exhibition, but also force cooperation between the galleries that required, beyond logistics of timing, etc, actually boring holes right through their walls! The reconstruction of the ancient dwelling was not done, in other words, in one gallery, but in two, and this required building supports across the two (or is that three?) structures, an architectural wonder further accentuated by the video projections of the “other” galleries constantly in view. Again, here Ai deftly captures long-standing questions of exhibition, space and viewership. We are complicit in uncomfortable ways, captured by cameras so we have a constant sense of watching and being watched in the simultaneously authentic and yet entirely artificial space.

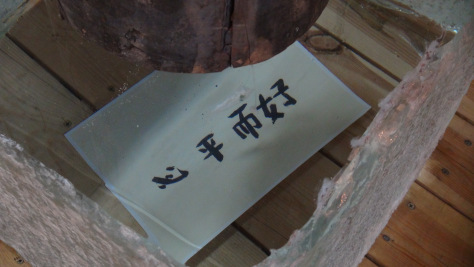

What captured all this most powerfully for me was the single footing, separate from the other (I presume) original pieces of support because instead of stone it is actually made of glass:

and a close up:

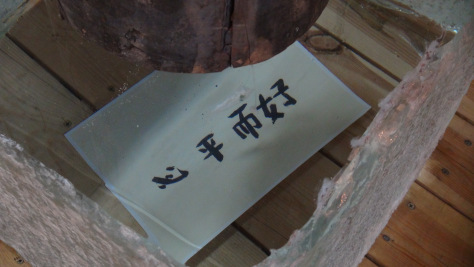

Apart from the obvious meditation on functionality and aesthetics of the built environment that such a choice occasions, Ai includes within the footing a note composed by his six-year-old son which reads:

心平而好, which literally could be rendered “with a peaceful heart all is well” but which might further be interpreted to say: F*** You! (to use a favorite Ai Weiwei-ism). Ai’s heart is not so peaceful, and yet he quietly and painstakingly assembles this massive work, supports it beautifully on an impossible sentiment encased in glass. I half wondered if at any moment the entire structure (and the two galleries with it) might not collapse at this very point. Fortunately that did not come to pass.

What the exhibition demonstrates for me is that Ai is a highly competent artist whose “issues” may not be as universal as worshipping media outlets would have us believe, but at least speak effectively to some core issues operative in China’s “rise”, for lack of a better word. In other words, if we must have celebrity artists such as this, I guess Ai Weiwei is a pretty good choice.