羊

羊肉

羊肉串

西夏

西夏王

西夏王酒

(中间代诗全集,下卷 1301)

The poem rendered literally:

Lamb

Lamb meat

Lamb kebab

Western Xia

Western Xia King

Western Xia King Wine

The poem, I suggest, lingers at the level of poetic method, not entirely deciding if its wants to be an image- or a word-based work of art. As word-based, it is still a form of graphic meditation on the materiality of “line” (as part of Chinese characters) and material world to which it refers. In this case, the geography suggested in the title bolsters the territoriality of the Chinese characters themselves, bordered, discrete spaces (“west”; “meat”; skewer”) just as they formally echo each other to the point of oblivion just as cultures in northwestern China contend and ultimately absorb one anther.

Following Qi Guo’s expression further into the visual, we can observe his performance of the single word “yuan” 缘 (something like “fate” but not quite):

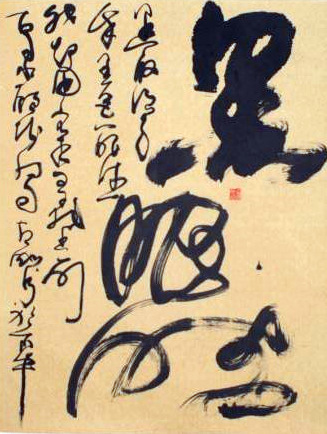

In Qi’s work I find another argument for long-standing modernist advocacy of “the Chinese character as a medium for poetry” (Fenollosa/Pound). Of course, with the above image we have slipped into the strictly visual. But looking at another work by an artist-poet of the same Contingent group, we have “Black Eyes” by Li Zhan’gang:

Li Zhan’gang 李占剛 is echoing the Chinese literary tradition in calligraphically performing a well-known poetic text (一代人 by 顧城)

黑夜給了我黑色的眼睛

我確用它尋找光明

The poem: 一代人 (“This Generation”)would be rendered:

The dark night has given me dark eyes

And I use them to look for light

What is striking about this to me is the way in which the tradition of re-inscribing a well-known poem can now be introduced into the realm of contemporary poetry. Gu Cheng’s work, from 1980s, was cutting edge at the time, and served to catalyze, along with similarly styled works by Bei Dao, Mang Ke, Yan Li and others, the introduction of new aesthetics for an entire generation of artists and writers. It is now possible to “return” to that work, to borrow from yet another medium, and “harmonize” 2009 sentiment (when Li inscribed it) with the 1980 “original.” This in effect gives legs to a now considerably more mobile visual-verbal tradition, one which evolves anew into the future precisely for its solid anchor in the past.