Given that so much of Zhong Biao’s art resides in the 妙 (a hard word to translate–“marvel-ful”?) of his juxtapositions, the unifying force of many of his images can be found in the title. Zhong does not use “untitled,” which might seem a reasonable approach given the degree to which the images seem to speak for themselves. Still, he chooses to name each one, and this process is itself worthy of note.

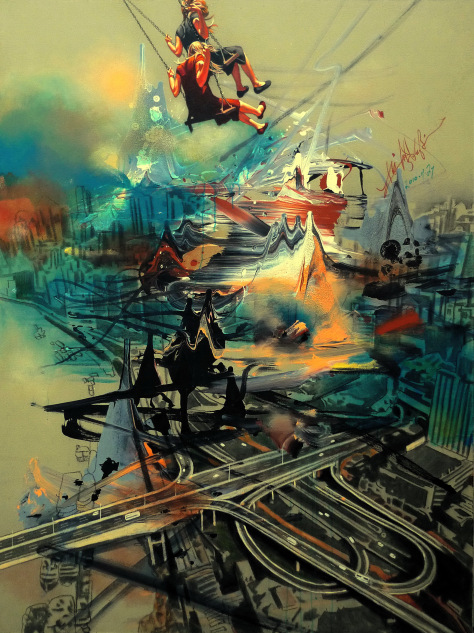

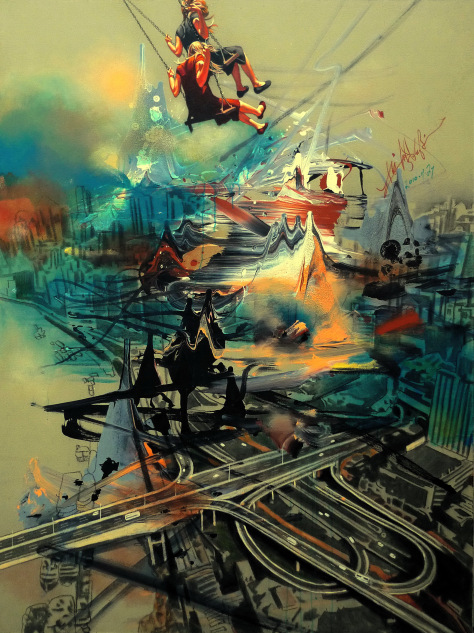

I think the titles can be roughly stratified into two general categories or better yet poles between which we could situate individual cases on some point of the continuum. The one side of the equation would be the relatively obvious correlation: a painting of a building entitled “building;” the other side the less obvious–a mess of strokes entitled, well, just about any—-thing. Most of what Zhong paints resides in a comfortable grey area in-between, with titles adding something to the experience of the painting, but rarely too much. Take, for instance, “Veil of the Road”

Referentially speaking, I wonder if the “veil” of this painting signifies to the blanket of pollution that covers most of China most of the time in recent decades. Zhong Biao is certainly a student of the sky, of light, of atmosphere, and he paints the limpid blue just as he paints the grey haze, with an exacting eye. This one, clearly, goes beyond haze, but also figures, in mad swirls, the kind of conditions that come with breakneck speed development.

Taking the matter a step further, into completely (?) abstract, is “Humid Season”:

Then there are the images which seem to conform in some obvious way, but on reflection one realizes that they are at odds, pulling the image in another direction entirely. Such is the case in “Roiling Landscape”

The landscape of “Roiling Landscape” is, literally in Chinese, “mountain water”, which suggests a posture vis a vis that natural environment that has a long history in China. Such a position is imbued with a philosophy, a way as well as a subject of painting. To shift to an urban scene, a snarl of highways, buildings, is to modulate out of this philosophical position entirely. This is particularly true in the prominence of the human figures swinging above it all, figures who from the classical painting point of view rudely upset the diminished, often nearly imperceptible place humans are supposed to occupy on the landscape.

Again, this image captures China’s development beautifully. The experience, which Zhong often paints, is not only one of flying, but one of falling, backwards, perilously perhaps. This was the joy of the swing when we were children (not to say they can’t still be enjoyed), although part of that joy was also knowing the thing was securely fastened. In the case of Chinese urban development that may be too much to assume. Thus, in translating 荡漾 I’ve chosen “roiling,” where something more like rippling would be more common. I think this image is a case where Zhong’s naming, his abstractions, and his urban theme come together for maximal effect.