Can’t say how many times over the years I have encountered the idea, while traveling in China and more particularly Beijing and more particularly still the Northeast district (Chaoyang), that the 798 arts zone is “dead.” Its been dead since shortly after its birth in 2001, a pronouncement made famously by one of its progenitors (I’ll resist the word “father”), Huang Rui. Huang was early on disgusted with the commercial/propaganda vehicle that the area quickly became once the Chinese government changed its original plan-to demolish the entire factory (built, for those unaware, in the 1950s by Chinese -East-German joint venture). Whatever Beijing authorities had planned at the time, no doubt it was not what turned out to be the most lucrative thing imaginable– a free, independent, international/global center for the production, exhibition and appreciation of contemporary art, both Chinese and non-Chinese.

The word “independent” here, though, is what caused problems in the views of Huang and others. Once the Chinese government got involved, there was immediately a chilling effect on the scope and of course content of the art created and exhibited. Meantime, and in curious lock-step with the increased surveillance and hence control of the artistic “message,” the commercial value of space in the entire 798 area rose so rapidly that most artists were priced out. Thus, it mattered little whether 798 was doomed for economic or political reasons, it was still doomed.

Or at least, such is the narrative. I’m certainly not going to propose that either one of those interferences with the development of an arts district is not in effect in the case of 798, but I still find, year after year, that visiting the zone remains a rewarding even impressive experience, where art of significant quality is on display in a density and variety that few places in the world (I know that’s a big claim–would love to be challenged on this point) can rival.

Here, then, a few rather pathetic shots from my own camera with a bit of commentary.

Outside

the first thing I like to observe at 798 is its edge. I love the ay the art and building come to an abrupt halt, here on the northwest corner. The installation of traffic mirrors to aid in safety a good example of something you won’t find often in Beijing, despite the fact that quote a few places could use them. The fringe of the above ground heating system, still wrapped in insulation, and the remains of whatever structural gate previously bordered the space when it was a factory district in the 1950s.

Here the makings of a typically elaborate exhibition, this one in the courtyard beside PACE Gallery, Beijing. Not a great deal to be discerned at this stage of installation, but typically arresting image of an airplane wing jetting up from underground.

798 Poeisis

This is one of the most interesting elements of 798 to me– the people who are constantly engaged in the incessant building, demolition and rebuilding that an arts district of this scale requires. I’ve often thought that if anyone really needed to obtain a thorough picture of what this place is they should contact whatever outfit sends workers in to actually make what we see visible. And then have a few sit-downs with the workers. One of these days I’ll find a way to do this.

the Inside:

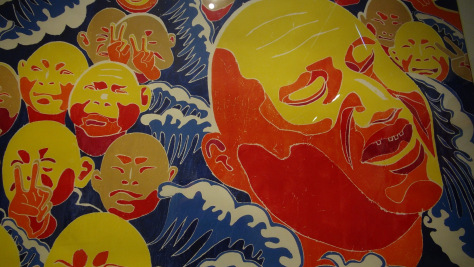

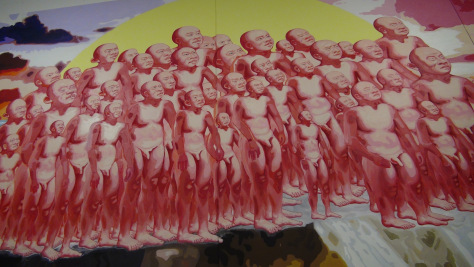

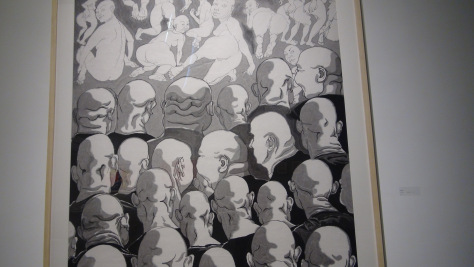

Too much to report on this at once. Here just a few shots from a Fang Lijun exhibition, which included both oil paintings and woodblock prints, demonstrating that his work is still current and suggestive. going on while I was there. More impressive still was the Ai Weiwei installation I saw, but I’ll write about that separately.