| 1968Chongqing, China. November 11, 1968. Even in the delivery room, people could clearly hear the sounds of firefights between the opposing factions “815” and the “Rebels to the End”. My mother had been in labor for eight hours, and then, finally, on the verge of her total despair, I was born. My father jumped for joy. At that very moment The Internationale was being played on the loudspeakers outside; the “Rebels to the End” were mourning their fallen comrades.The couplets on their wreaths read: “The song of The Internationale is for mourning, whirlwinds from heaven have reached me.”This gave my father an idea about my name. “Biao”, whirlwinds, thus dropped onto my birth certificate.1969The sounds of gunfire gradually faded away as the three-year conflict finally came to an end.1970

I said the word “Great!” and made all those sitting around me jump. This was the first meaningful word I uttered.

1971

October: at the 26th session of the United Nations, the People’s Republic of China was restored to legitimate sovereignty.

1972

I remember that I began drawing by tracing illustrations from children’s books.Although those early works have already turned to dust, the encouragement I received from them remains fresh in my mind.

1973

Encouraged, I began to fall ever more deeply in love with drawing.

1974

That day, after we got home from seeing Shanggan Hills at the open-air cinema, my father began to describe to me with excitement the fierce battles between his battalion and the enemy’s in only four square kilometers of highland. “That communications man in the film is me!” he claimed. “How come he doesn’t look like you?” I asked, only half believing his story. My

mother explained, “Silly, your father is one of the characters the film is based on.” My father continued, “Back then all we wanted was to go back home and live in peace.”

The next day my mother made a sumptuous dinner – a rarity for us – consisting of one meat dish, two vegetable dishes and a soup. We lived in difficult circumstances back then, so the sumptuousness of that dinner made a deep impression on me, and became a symbol of peaceful living in my mind.

1975

I started school in fall. Jianxin primary school was situated on the banks of the Jialing River.The shouts of the boatmen frequently penetrated the classroom walls and led my thoughts away from class.

1976

On September 9 our teacher ordered us not to play or laugh, because Chairman Mao had died. I was really surprised; I always thought he would live to be ten thousand years old. On October 14 the “Gang of Four” was smashed;so lots of cartoons and pictures were needed for the blackboard newspapers.

I participated enthusiastically and clearly stood out from my classmates. Afterwards I was recognized as the most talented artist in my school.

1977

“Let’s pick up our oars, the little boat pushes through the waves, the white pagoda’s beautiful reflection dances in the water, red walls and green leaves surround us.The little boat floats on the water, greeted by a cool breeze…”.This is the song that accompanied my childhood joys and hopes.That year the college entrance examinations resumed.The door to college would open

for me ten years later.

1978

The third session of the eleventh Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee was convened in Beijing. The Committee pro-

posed that we put all our efforts into developing the economy. China began to open up.

1979

On January 1 the People’s Republic of China established diplomatic relations with the United States of America.I’m not sure when it began, but the gentle voice of Teresa Teng gradually started to ripple through Red China.

That year I was diagnosed with Hepatitis A. I thought I was going to die. I developed two distinct fears.The first was that I would leave nothing behind after my death, that I had wasted my life. Pride is to blame for that.The second was a fear of death itself. The idea was just too abstract for me. After that, I tried to write my autobiography, and failed.

1980

The migrant bird was on the move.Without even noticing it, I had finished primary school.

1981

The Chinese women’s volleyball team won theWorld Cup for the first time.

Across China, everyone was excited by the slogan “Rouse the Chinese people”.

1982

My grandmother followed my grandfather to the grave. As she was sent into the leaping flames, the word “death” sprang from the dictionary into my mind. Not long afterwards I turned fourteen.

It had been six years since the end of the Cultural Revolution. As “Scar Art”shifted to “Pastoral Painting” I visited Sichuan Fine Arts Institute for the first time. Moved by the paintings I saw there, I began to veer away from the scientific career my parents had in mind for me.

1983

I was admitted to the secondary school annexed to Sichuan Fine Arts Institute.

1984

I was fifteen and a half. L sat in the row of seats behind me; I could always feel her gaze all over me, from the crown of my head down my spine. I was happy imagining that. As we spent more time together I became aware that we were growing closer, and I became too shy to look her in the eye.

My classmates in the upper classes often talked about the things that go on between boys and girls. I was confused; I didn’t seem to be getting anywhere, but in the end I couldn’t conceal my growing infatuation and asked her out. She refused, giving the excuse that she was going to see a painting exhibition in Chengdu. That made me hate whoever organized the show.

Later I found out the show was about the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch.My teacher advised me not to dwell in my frustrations. I gritted my teeth,and told myself to “Struggle on!” At the end of the day, this battle cry, struggle on, is the most precious gift L gave me.

In December of that year, the Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed,stating that China would regain control of Hong Kong in 1997. I had no idea then that my first solo exhibition would also be held in Hong Kong in 1997. I thought of Munch, whom I had hated, and his Scream.

1985

This was the year thatWestern thoughts came rolling into China, and everyone wanted to go study overseas. It felt like the May Fourth Movement was experiencing a resurgence.The campus was brimming with May Fourth sen timents, and I was swept along by the excitement. So much so that it literally whetted my appetite. I once even ate a kilogram of rice.

1986

That lunchtime the sun was shining so brightly, I had trouble keeping my eyes open. I arrived at the gallery without quite knowing what I was doing there. Rembrandt’s paintings moved me. I was awestruck. I thought to myself: “I don’t just want to appreciate them, I want to paint them.” Then I heard someone say: “Idiot!These paintings belong to you.” I turned in surprise, but could not see who had spoken. Yet I believed it was real. I didn’t want to wake up from the dream, but in the end, that’s all it was. A tanta-

lizing mirage.

I felt dejected, but then I had another idea: those paintings were not Rembrandt’s.There was nothing else like them in the world; perhaps they really were mine – my future works. I quickly tried to capture them on paper, but the actual images faded swiftly. The mirage was fading away! An aesthetic idealism emerged from my confusion: I was totally convinced that those paintings were my purpose in life, my dream.This idea has stayed with me and has become increasingly clear over the years.

1987

Time flies. On the night I left secondary school I received a gift package from the “secret Santa”. It was from K: the package in-

cluded a pair of socks, a cowry shell and a sea snail shell.

Two places hold sentimental value for me: one is Hangzhou’s West Lake, the other Tiananmen Square. In my mind, the first

is like a contemplative, beautiful maiden, and the second a robust and powerful man. One day in August I received my letter of acceptance from Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou. It turned out I’d be going to see the maiden.

When I met the maiden, I found myself instantly entranced by her tranquility. The scenic spot called the “Oriole in the Willow Waves”, located opposite the campus, was like a glass of fine wine that intoxicated me, as did the year 1987.

1988

My home was far away on the horizon, and West Lake was an intangible,floating dream.

I became quiet and introspective for several days. On my twentieth birthday,for no particular reason, I wanted to have a stiff drink, and drink I did. I went to the scenic spot called “The Broken Bridge with Melting Snow”, and felt alone and miserable; it was extremely cold, and I cried and felt something stuck in my throat. For a long while I could neither spit it out nor swallow it, and I decided that this was “suffering”.That recognition made me happy.

But I was frightened by the latent tendency for self-punishment in finding happiness in suffering.That moment came to symbolize 1988 for me. I was terrified when I realized that becoming an introvert could prevent me from being happy for the rest of my life. I decided to climb out of self-pity and introversion. It was W who helped me.

1989

When the bells rang in the New Year, I had no inkling that 1989 would be such a turbulent year.

I spent all my time painting until mid-January. I met Mr. Lin in the lobby of the Lakeside Hotel; he said he wanted to arrange an exhibition for me in Taiwan, and counted out a pile of notes for me. I put my hand on my heart,and felt it thumping. I sent some of the money to my parents, and the receipt from that transfer became my declaration of independence.

On April 15, the general secretary of the Communist Party of China, Mr.Hu Yaobang, died. That day I invited W to climb a mountain that looked steep and dangerous, and she said yes. We set out the next day. Although it was steep we managed to find our way. At that time in Beijing, in places like Beijing University, Beijing Normal University, Renmin University, and the China University of Political Science and Law, students were gathering to march on Tiananmen, in memory of Hu Yaobang. Around midday we reached the top of the mountain.The peak was like a stage; from far in the distance, we could hear a sound like waves beating upon the shore.

On April 18, a group of teachers and students from the universities in Beijing gave a list of requests to the standing committee of the People’s Congress, demanding a re-evaluation of HuYaobang’s achievements, and an end to the political campaign against the so-called “bourgeois liberalization”.Only when I returned to campus did I find that universities all over the country had suspended their classes. People were waving banners and marching in protest all over the place. It was like a scene from a movie.

On April 26, the Renmin Daily published an editorial with the title “There must be a firm stand on opposing upheaval”. After that, three thousand students went on hunger strike inTiananmen Square, while the media became increasingly sympathetic with the students. It was the first real political lesson of my life.This is when I fell in love withW. I had thought that we were poles apart; after spending time together and looking after each other, however, we were like two peas in a pod. Later I used my experience with W to observe the things around me, and discovered that almost every barrier around me could be removed.

On May 20, the Communist Party of China and the State Council announced a state of martial law.The conflicts grew ever more fierce. On June 4, the army drove intoTiananmen Square and suppressed the rebellion.The state media claimed that the country was stabilized.

Three years later, when I stood on Tiananmen Square for the first time, no trace remained of the “June Fourth” Incident. It was a crisp, bright fall day.

My childhood idea of the Square was right: it truly was like a powerful male presence. I would continue to think of it that way.

On September 9, the Berlin Wall dividing West Germany and East Germany collapsed, and by October 3 of the following year Germany was completely reunified.The Cold War between the East and West gradually came to an end. That year saw the world powers in turmoil. The storm raged on all sides and in all lands.

In the summer I traveled by myself all over China. I was struck by a quote that I had copied down: “If a traveller sets out to find the ‘other’, he can only achieve this by becoming one with it.”

On New Year’s Eve I felt so relaxed after my shower, I was unsteady on my feet.When the bells began to ring, I said goodbye to a turbulent 1989, and to the Eighties. They had passed away, never to return. I have no idea how many things I have forgotten in the heat of the moment. Perhaps I will remember them some day, and perhaps they will change the direction of my life. I only know that the pain we bury deep in our hearts will, in time, become a testament to our life experiences, and will transform into something precious, like a mellow vintage wine with a fragrant bouquet, that we can find solace in during our twilight years.

1990

I watched The Last Emperor for the fifth time, and for the fifth time I felt a burning desire to paint. One of my paintings, Sports Education, was selected for the Second Chinese Sports Art Exhibition at the China Art Museum in Beijing. I shaved my head, to show that I was starting from scratch.

In September I arrived in Xi’an and set off on a journey to visit places of cultural and historical importance. From Xi’an I went to Lintong, Xianyang, Fufeng, Fengxiang, Linyou, Baoji, Tianshui, Maiji Mountain, Mengyuan,Fengling Crossing, Ruicheng, Tongguan, Luoyang, Suzhou, Shanghai and Hangzhou. On the trip I was transfixed by the weight of history. As I stood,awestruck, in front of the Yongle Palace murals, a word came to me: time.

Decaying, windswept, faded, peeling, blasted, chipped, and damaged by wars, these murals were created by both man and nature.Time had made its mark on the murals, and altered their original meaning.The murals were like a great memoir that records the passage of time. I thought of another example. Li Yu of the ancient SouthernTang Dynasty once wrote the lines: “I ask you, how many troubles may there be in this life; it is like a river flowing East in the Spring.” A thousand years later, people still find comfort in this poem, because it speaks to their own pain.The appreciation of art is in itself a creative process. Because of this, I realized that a piece of art work should leave room for the viewers’ re-creation.The work has no lasting value

if it is too perfect.

On November 28, China officially joined theWorldWideWeb when it registered its own domain name, CN, with the International Internet Information Center.This move opened the floodgates.The internet waves swept through China overnight.

On December 19, the Shanghai Stock Exchange opened, and the Chinese Stock Market was launched.

1991

After I had finished my search for cultural relics, I felt like I was pregnant.Ten months later, I “gave birth” to three paintings: City Passers-by numbers 1, 2, and 3 became my graduation pieces. During our graduate exhibition,I experienced an intense feeling of separation: those three paintings were like my children, but they had their own independent lives now, and were no longer a part of me.

When W found work in the South, she just told me, “I’m going.”One summer’s night in August, I sat at the foot of Yuhuang Mountain in Hangzhou and read philosophy. When Zhuangzi, Laozi, Confucius and Mencius had finished brainwashing me in turn, I looked up at the stars.The air was thick with the sound of cicadas.The constellations raced along their courses at a speed undetectable by human vision.They were higher than the planes in the sky; the planes were higher than the Himalayas; and the Hi-

malayas were higher than me. Height can only be measured from your own perspective.The struggle to be the highest now seemed meaningless. It was more important to me to find my own position and direction. Perhaps this also explains why my first word was “Great”.

That September, I took up a teaching post at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute.The day I arrived, I was full of energy and idealism. I thought I was going to conquer the world.In the end it was Miss K, my secondary school classmate, who struck the first blow to my confidence.

On December 21 the Soviet Union collapsed, just five days before its seventieth birthday.

1992

When I married Miss K, I rummaged through my belongings and found her present I’d drawn in the “secret Santa” game five years ago when we graduated from secondary school.The snail shell and the cowry were like the two halves of a magic yin-yang symbol; I broke out in a sweat. It seemed all had been planned out without our knowing, a long time ago.I found a vase in a pawnshop and instantly handed over five months’ salary for it, believing it to be a genuine antique. Although I later found out that it was a fake, the finding inspired my love of antique collecting. I wished that time would run backwards, back to ancient times.

Miss K and that vase jolted me out of my lofty artistic idealism and brought me back down to earth.I liked the reality check. I began to live like a normal person.Just when it seemed uncertain what direction China would take, Deng Xiaoping went on a tour of the South and proclaimed: “We’re dead if we don’t develop our economy.” The progress of reform and openness could not be turned back.

1993

It was a remarkably average year. In fact, you could say that I sleepwalked my way through it. Perhaps my high hopes for radical change had made me cynical – but you can’t expect a child to see through the futility of the world,even for someone looking from up high.

One morning, I dreamed I was seventy years old, with little time left to live.“I have nothing to show for this life,” I thought. I awoke from the nightmare sobbing. “Thank goodness I’m only twenty-five!” I wiped away my tears.

1994

Having survived 1993, I burned nearly one hundred of my sketches. I finally completed two series, Travelogue on a Dressing Table and Nostalgia Series. I was relieved. It felt like my life had meaning again.

That year, I finally realized that K had dreams I could not fulfill. She was like a helium balloon, ready to fly, and I was holding the string, holding her back. I was scared that if I let go, the balloon would fly so high that it would burst under the pressure. I couldn’t bear to watch her suffer.

As for K, her dreams were also her tragedy. Dreams are the tragedy of all modern society. The traditional model of family life has become outdated,but we have yet to find a replacement. Nor can we satisfy the basic demands of the human mind.

1995

Our marriage ended during the burning hot summer.

1996

On the morning of November 18, after countless days and nights of work,I took my paintings to the exhibition hall of Sichuan Institute of Fine Arts.Relieved and exhausted, I returned home and fell fast asleep.The next day I returned to see my works. I realized that my recent paintings were all connected by a common train of thought and spiritual direction.

From City passers-by to Travelogue on a DressingTable, to my current works,they were all connected.The only difference was that my current works were“dressed” differently, in “clothes” that fit them better.

Maybe it was in that moment, when the afternoon sun shone so brightly that I squinted, that I realized that my paintings had so fully become a part of the paintings in my dream. I finally understood: the mirage was the “other” that I had searched for and sought to combine myself with. I was shaken by this realization, because my paintings simultaneously express and symbolize the

state of my existence.

The above was completed in February 1997, at 184 Huanxieping, #7-3,

Chongqing

1997

My autobiography was halted for twelve years. In 2009, I went back to 1997 to recollect my memories of the past twelve years. My 2009 self had to slip back into the body of the previous century. Far from feeling enthusiastic, I found myself lost for words and my thoughts frozen. Only by living in the present does one have a body temperature, a metabolism. Memory plucked me out of my body, and flung me back towards the abyss of the past. I became one of the walking dead as my heart and body were divided.The difficulty of writing as the walking dead was caused by the year 1997.

Approaching me was the news of Deng Xiaoping’s passing away on February 19. This was a great man who re-orientated Mao Zedong’s utopia in line with the trends of history. I also saw the opening of The Fable of Life, a solo exhibition by Zhong Biao at Hong Kong’s Schoeni Gallery, which officially kicked off a career in art. Spring that year in Chongqing was bright and sunny; hope flourished wantonly in Zhong Biao’s heart, and his body opened up like an ornate kaleidoscope, through which one could see a se-

ries of historical events: Hong Kong’s handover, the Asian Financial Crisis,Dolly the cloned sheep and the funeral of Diana, etc. A mosquito took a vicious bite out of the leg of the walking dead who was looking into the kaleidoscope, and I was back in 2009.With a flick of my hand I transformed the mosquito, engorged with my Type B blood, from a solid into a planar object. My thigh looked like it had been tattooed! My memory had opened up.

1998

A sunny spring day, in a teahouse beside the Yangtze River in Chongqing.Elderly men, their years each numbering more than half a century, were playing chess. I was lost in thoughts that melted in my jasmine tea. I felt directionless. The bright day turned overcast: a rain storm was approaching.

A storm was brewing in my mind too. Suddenly, lightening struck: among all of life’s contingencies, there must be an order; why don’t I work with that order hidden behind the coincidences in my art?

Mid-summer. An acute bout of gastroenteritis forced me to wonder why one should giving one’s all in the present for a wonderful future?

Deep fall, the twentieth year since the opening-up of China, the thirtieth year since my birth, nightscape on the banks of the Huangpu River drew to a close. I sat alone on the bund in Shanghai and could feel the vigorous beating of the pulse of the times.The waves broke darkly, the evening breeze caressed my face, the emotions were like chili pepper, and my tears were

pungent.

Mid-winter, nothing worth remembering.

1999

In 1999, three private art museums were established by industrialists in mainland China.Their initial collections were contemporary art, primarily destined for export to the West. That was a long seven years away from the red-hot market of contemporary Chinese art. During those seven years, the museums vanished one by one.

In February, I got steaming drunk for the second time in ten years. Having made sure that I was safely lying face down on the floor, I decided not to dwell on the painful memories of the past decade, but to move on. That day, the clouds in Chengdu turned into sunshine. That year, from a phonecall on the People’s Square in Shanghai, to wandering thoughts upon the Chengdu-Chongqing long-distance bus, from the late-comer on the international art scene, to a duel of words at the Xinhua Hotel… Real lives were turned into secret codes, which were better suited to being locked in their own separate drawers.

2000

From the first year of the reign of the Ping Emperor of theWestern Han Period (AD Year One), to the third year of Xianping of the Northern Song Period (AD 1000), there was no connection between our ancestors and the confluence of the millennium. Real time and calendar time are totally different things. We arrived without explanation at the year AD 2000, as demarcated by the birth of Jesus. Although the new millennium had sparked fireworks and excitement all over the world, the moment itself was low-key and ordinary.The transition to the new millennium was less noticeable than the change between night and day. The last three digits of the year all went to zero, the millennium returned to zero, and yet the moonlight remained unchanged.

MissT, who is a completely different kind of person from me, walked with me upon the waters of Qinghai Lake, frozen in the winter. Between the banks, layers of surging waves had been frozen into immobile statues, like rapt passions hibernating in the sunlight. At the sub-district office we got married.

2001

The true beginning of the new millennium, 2001, made a low-profile arrival.Way back in time, in 2000 BC, the city of Ur in Iraq was the most prominent city in the world. The world’s most magnificent cities form a chain,each enjoying five hun-dred years of prosperity.By 1500 BC the most prominent city was The bes in Egypt; by 1000 BC there was no center to the world;by 500 BC it was Persepolis; by AD 1 it was Rome; by AD 500 it was Chang’an (Xi’an);by AD 1000 it was Bianliang (Kaifeng); in AD 1500 it was Florence; in AD 2000 it was New York.That string of bright pearls reveals the nature of history, which is to develop with disregard for human will, therefore no one knows what place will be the center of the world for the next five hundred years to come.

On September 11 two planes hijacked by terrorists crashed into the WorldTrade Center; theTwinTowers collapsed to the ground, and 3,025 people were lost. Peace was attacked by yet another enemy, whose name was terrorism.

Although it was my first visit to Europe, it felt like a reunion. The scent of plants, perfume and Jesus mingled in the air, as if it had been buried in my body all these years, only to be reactivated after the Cultural Revolution,the reform and opening-up of China. In a small town in Germany I ordered a double espresso. On December 11, China joined the WHO.

2002

As I dashed up to the peak of the pyramid, my stomach was churning and my mind was fogged up by the sights and people around me. It must be altitude sickness! My paintings were greeting the audience at the Post Office Palace in Mexico City.The Long March Project had reached Lugu Lake; as part of the project, an exhibition of female artists was curated by Judy Chicago. The show was at Lugu Lake, which still remains a matrilineal society! I passed myself off as a woman and sent in the poster piece 8th March.

Amazingly, Judy Chicago actually identified it as the work of a man and revoked my right to enter. How perceptive she was! Her critical sharpness made my altitude sickness worse.I went to the home of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo; they were not there,

there was no one in the studio either. People said they left during the previous century; the ladder hanging outside on the wall went up to heaven.

I went to the Three Gorges on the Yangtze River. Millions of people were forced to move to higher elevations. The long boat whistle was like a resonant fart mixed with music, sending masterpieces to the bottom of the waters. There was no Li Bai amongst the ruins on the shore.

This year, contemporary art was already being drummed up on various battlefields in China, advancing from the boundaries to the mainstream, forcing art education to a crossroads. “The great trend of the world, those who follow it prosper, those who oppose it die.” Sun Yatsun’s voice traveled over from the beginning of the previous century, with a distinct Cantonese accent. In September, at harvest time, the Beijing Agricultural Exhibition Center’s Contemporary Art Exhibition pushed experimental art before the million-strong audience of an apple festival celebration. By this time everyone was growing accustomed to the stunts of the apple sellers while using this temporary stage to furtively ferment a new cultural plan. That is the path that any underground new wave trend must take.

On October 28, Chongqing Art Museum was founded on the campus of Sichuan Fine Arts Institute. I couldn’t believe that the first proposal I made as Deputy Director of Creative Research was accepted! The opening exhibition was organized and mounted. I had eyes like a panda from the late nights, and all of the pieces of artwork looked like bamboo shoots.

2003

I returned to my Alma Mater for the Institute’s anniversary. It now has a new name, the “China Academy of Fine Arts”; the new name and the new buildings helped erase the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts from my memory.

The traces of the past floated in the wind, unable to find a resting place, at odds with everything. Fine then, let us leave the past behind and embrace the future without any burden of the past.

Anthony Gormley led an army of more than 200,000 little clay figures,bringing the art project Field to the multitude. After curating the Chongqing leg of his touring exhibition, I read the vast amount of messages left by the audience and had to marvel at Gormley’s universal appeal: his art does not require the audience to have any professional knowledge or cultural decoding, and can easily relate to everyone’s feelings and emotions. China’s famed“Clay Zhang” couldn’t hold a candle to Gormley because Zhang’s figures were impersonating life, whilst Gormley’s clay figures were a link to real life,a vestige of collective consciousness.

2004

At the start of the year I went to Jingdezhen to look for the glory of the past days of the capital of porcelain. Jingdezhen was like a fallen noble; every lamp-post on the motorway was adorned with a porcelain encasing decorated with blue and white dragon motifs. It was vulgar in a straightforward way.The thousand-year-old art of Chinese porcelain has become a precious relic, while the mainstream of porcelain has moved onto toilet bowls and bricks. In fact, any carrier has its ups and downs, there’s no need to feel troubled by it, because the spirit continues. Just as Taoism outlives Laozi and Zhuangzi.

A new demand and supply chain was developing in mainland China: business expansions must have a broad base, and, by extension, experimental art must have popular appeal. My friends and I curated a show called No Distance – 2004 China Construction Site Avant-garde Art Exhibition.True to the title, the show opened on April 17 as a construction site and attracted several thousand people who normally would not be interested in an incomprehensible avant-garde show. The crowd made the opening feel like a

temple fair.We were all surprised. Originally we had planned to work alongside real estate developers and each gain our own benefits. No one had imagined that the general public’s eyes were bright and brimming with enthusiasm towards avant-garde art. I recalled the words “No Distance” in the introduction: “No” means emptiness, zero, hidden, void, negative, dissolution, the un-begun, and the already complete, the formatting of all content, the return of supposition to supposition, reality taken back to its start,a tolerance that accepts all things, great or small without question, a conclusion without having found the answer, openmindedness with no standpoint of its own…it could be more things, but moreover it is nothingness itself. “Distance” is separation, division, the space where objects blend together with each other, the collection created after categorization, the na-

tivism within globalism, the plain and spicy soups in a hotpot, the line between dreams and reality, the distance from here to there, the transition of one type to another, a pause that continues to explain itself … it could be more, or it could just be an inspiration following the structural breakdown of the character “distance”: living a life behind the door.

2005

It was time to leave the post of administration. In Chongqing, the cultural dream I anticipated had not yet reached a level where it can be put into practice, but the seeds were putting forth shoots, whilst the great tree would be bathing in the sunshine of the future.

The sky grew dark over Huaihai Road in Shanghai, bringing on the streetlights and neon. The busy crowds moved in the direction of their individual dreams. A giant painting of mine hung high on the outer wall of the Paris Spring Mall in Shanghai. I had never imagined that my work would appear in the centers of several large cities. And Dragonair were using my art to promote their image.

Using a style established ten years before to meet the demands of the masses of the present, I became the living proof of the time difference between the avant-garde and the fashionable. In time, the masses will adopt the avantgarde ,andmakeitfashionable. Whatisfashionablewillbecomeclassicalwith the passing of the years. It is an endless chain of life: as time diffuses the rage of the avant-garde, it gives birth to new rebels; as time dwindles away the moment of enthusiasm for a fashion, it produces new cravings. Finally, the essence of the popular passes into the classic, glittering in the night sky.

It was an average Chinese New Year. Life had changed before the fireworks fell silent. But what I had not expected was that the major change came not from reality, but from the metaphysical.

My art and life suddenly came together! Art was no longer an onlooker on life, it no longer struggled for my time, no longer approached my desire with an attitude of loathing; and life was no longer the resource library of art. They were one and the same, with no delineation. The realization that art and life were as one in my heart had gradually torn away the mysterious veil from the confused world.The logic and traces hidden beneath all kinds of things rose to the surface, and I took to it like a duck to water. I didn’t know whom to thank for this change, and so I could only turn my grateful heart towards all the things around me. In the chilly spring air I saw another layer of true existence, the world of energy! It has always been there, it is the raison d’être of all things. Because it has different spatial-temporal coordinates, its existence lies beyond our comprehension, like the world of the internet once was. In fact, the networked worlds had been in existence millions of years ago, it’s just that we had not found the paths to them. Once the conditions are in place, the worlds appear immediately. In the world of energy,we have gone far, passing through innumerable centuries to reach the present moment of this life.We can never go back! And so we can only naturally take shape wherever we find ourselves.

In the real world, roses wither quietly in the bar, music and desire exchange energies.

2006

In the spring 2006 issue of Hermès World, my essay, “Fragments of Paris”,was the cover story, and was and translated into twelve languages. This was a big deal for me, consider-ing that I could not speak French and had spent only twenty days or so in the country, including layovers at the airport. For someone like me who is not a writer by trade, writing an intimate essay about Paris was even more difficult than a blind man feeling an elephant. At the magazine launch party on April 6, the head of promotions for Hermès said, “I was born in Paris, thank you for describing to me a Paris I didn’t know.” I replied, “I’m glad that I was able to recuperate my

original feelings about Paris during the process of writing this essay.” At that moment, the elegant sound of a male tenor drifted over, “Paris, a word hidden in the encyclopedia, when I find it I follow my feelings…”.

Whether we travel from Beijing to Chongqing, or from New York to Istanbul, from the city to the country or from a foreign land back home…we are faced with the same planet, the only difference is that we see it from different perspectives.That is why it is possible to draw nearer to reality while on the move. Movement is not only geographic, it is psychological.

I arrived alone in New York at dusk, the treble voice of a police siren breaking through the confusion of sounds on Times Square. Visual shocks were like tidal waves to me! “Times Square” is a name that at once includes time and space, in a fantastic realm, describing life as a story passing through time and space, and then departing. After a few days, I looked out of the plane from New York to Denver, the floating white clouds over the broad earth were like unpicked cotton, beneath the cotton a meandering river poured forth a song from the depths of memory, “A great river with wide waves,the wind blows the scent of flowers from the river banks. I live upon the river bank, I’m used to the sound of boat people singing, I’m used to the sight of white sails by the banks…”.The songs of nostalgia from the Korean War were being sung by the lost souls of the opposite sides in what was once enemy territory; peace was listening.

2007

On July 25, 2009, I found I was, to my surprise, referring to myself in three different ways. So I couldn’t help but try to use this in my 2007 autobio-graphical writing. It was like this: Zhong Biao includes you, me and he,three forms of existence, you are living in the real world, I exist in the realm of energy, and he – Zhong Biao, of the past and the future, is always passing through our bodies, round and round.

Now, you are Zhong Biao! We already know that on the afternoon of January 1 you arrived in Beijing with T; the sun was shining brightly, engulfing the brilliant white snow, melting it into slush, and there was the de-sire for a new life.

Starting that,would from Beijing become finally returned to the world of energy beneath the real world, dizzying high-

speed transport controls everything in the real world.

You’d only been in Beijing for four months when I told you, “the trends of history do not move according to the will of man, rather man must move with the flow in order to achieve great things.” You broke into a cold sweat,thinking of those years in office.When those conservatives wished to return to the past, you were pointing to a future that had yet to occur. Whichever you were, a praying mantis stopping a cart or a praying mantis pushing a cart, you were way over your head! “All of our knowledge goes into finding a way to go with the path of nature.” In fact this sentence appeared earlier,from your pen in 1999, but it was lost in 2002.

You were in the ice and snow of the Red Square, searching for the red dream of the Soviets, which had at one time been written in your secondary school textbook, and now you could only catch the strange scent of it from the Political Pop Art of Russian artists. Socialist China had just proclaimed the“property law”, and in Chongqing the coolest eviction resistance in history created a strange sight. The lone-standing house was like an island created by a lake drying out; it was an artistic masterpiece rising to the occasion of

the moment. You know it, I know it, it’s just a shame the family resisting eviction don’t know it. The nat-ural creation under the effect of various factors is a piece of artwork without a signature and will disappear outside of the walls of a museum.

I see you wearing a white shirt, smiling reservedly as you move about on September 1. Your solo exhibition Beyond Painting opened at 798, Beijing.I returned to the real world to enjoy it with you, to share your experience. I followed you to Hong Kong, Moscow, San Francisco, Madrid,Taipei, Seoul, Singapore, Athens, Dusseldorf, Essen, Cologne, Jakarta, New York, Denver and many more cities. You say that Beijing is close to the world. I say that Beijing was a part of the world all along.

On Christmas Day you arrived at the mythical Dali, white clouds in a blue sky, Cang Mountains and Erhai Lake clear without a speck of contamination, as if unused, remarkably new. Your mind and body began to grow transparent and vacuous, ready to walk towards the 40th year of your life in a clean slate. I rest a while, I too will enter the certainty that is 2008.

2008

In a flash, forty years have passed since the afternoon when Zhong Biao was born. Only afterwards would I know that 1968 was an eventful year. Time Magazine even went so far as to say, “the year 1968 was like a knife, slicing between the past and the future.” Of course this is no attempt to bolster up the birth of Zhong Biao, just a forty-year-old child wanting to tear open the withering past like a birthday present and spill its contents upon the floor.

The massive changes that took place in the thirty years since the reform and opening up of China were like another world, and memories of childhood were like a distant legend.

In “Setting Out from 1968”, this narrative is strewn with secret codes. Life experience makes a potential choice of music keys, choosing this or that, rising and falling in succession. Are the keys that decide the past the aesthetic needs of the present, or the requirements of a writing style? Is it a calling from the bottom of one’s heart or dressing up in another’s eyes? Or perhaps it is the natural revelation from out of the black hole of energy? No matter what it is, when an old tune is re-written into a new movement of the symphony, it gains another level of truth. At that moment it walks a step at a time out of the depths of the darkness.

This year the 29th Olympic Games was held in Beijing. The long-brewing global financial crisis burst forth from Wall Street, another underground force caused the 5.12 Wenchuan earthquake. Forty years after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., America elected its first black president,Barack Obama. Everything has always existed and only reveals itself when paths cross.

On September 6, your solo exhibition Revelation opened in Shanghai, this fateful signpost on the road of life appearing as scheduled. In the depths of reality, the past, present and future are a pre-existent entity, and when we pass through we are entering upon a part of that entirety. Ever since then,I’d often see you in broad daylight using the language of humans to describe the secrets of the world of energy. And when you are enjoying yourself with your brothers and sisters, you need me to show you the meaning behind it.

At the bonfire this Christmas, not only was time and space ignited, I suddenly realized that you had returned to a time before the birth of images.You can reveal yourself in whatever form you choose, you can switch between self and others, you can slow down your gaze to capture the remnants of the image, you can change music into an animal and let it burrow into your body, you can make dance flow in a liquid state, you can use the extremes of darkness to set off the light, you can melt time, you can make breath reveal itself, you can move distance and make the ends of the earth close to home, you can alter the movement of the sun, moon and stars, you can create your own universe…everything returns to the state of chaos, and in that state anything is possible!

Your experience of extreme bliss moved me as well. In fact, life is an innumerable pile of still lifes, linked together by your wishes.To

create a movie as long as life itself, that continues to play without stopping for even a moment, even when you take a nap on the sofa, that too is a necessity to the plot. And in the seats of the audience, as well as myself watching you,there is Jehovah who has just had his 2008th birthday.

2009

The Revelation project indicated a return, a conclusion of the relationship between images. In the cold winter of Beijing, art had brought you onto the path to meet with me,on this journey towards chaos, to seek the source of energy behind the birth of form. “Only by following the eternal trend of certainty can artistic creation be reborn in each new present time,” you proclaimed in Jakarta, at the opening of The Tendency of Events, when the rain began to fall.

On the motorway driving from Beijing to Chengde, you turned up the volume, the music piercing through the depth of the night. Suddenly the scene began to move with the mind! The car ceased to move, and the road moved in reverse.The changes outside the car windows were near or far, fast or slow, using tempos and rhythms to transform the earth into a dancing animal. This animal called the earth is your friend, and in that warm spring afternoon it revealed the music through its dance.

The sleep of the spring knows no waking, but you began to cut the hours of sleep despite how much you wanted to sleep. It’s not that you were responding to the empirical rule of “can’t wake up for the first thirty years of life, and can’t get to sleep for the next thirty years”, but rather that you felt reality was too wonderful to sleep through. As soon as you opened your eyes you would be greeted by a new day’s vitality.When you changed your point of view you saw that since the physical sphere of life can never leave the circumference of the body, it is in fact our surroundings that change the background around our wishes, creating a life that remains unchanged in the face of myriad changes.

In the early hours of July 7, your father passed away right under your watch.The sorrow that had been determined since your birth appeared as if on schedule, just as your hidden energy surged within you as never before. But the energy in your father’s body was leaving him, as if there were a tube between your two bodies. As your father went higher and higher the flow of energy came flooding down towards you, until he was dried out, and rose to heaven in blazing flames. From this moment on my father is in the night sky.

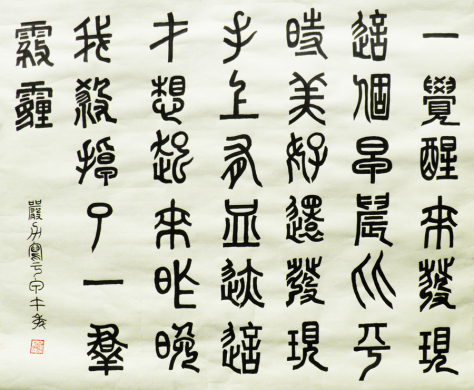

On the road once more, setting out from the depths of interstellar space, all dark matter gradually transforms into history and reality, converging into a mixer called art. Body and soul knit closely together, after the turbulence, finally condensed into your huge new artwork, Mirage, revealing the secret rotations of the latent trend, and the multifarious scenes that swirl above it.

You put down your paintbrush on October 11. It was as if you’d turned into a transmission device. In a second the past and the future Zhong Biao returned to the present mind and body, a reincarnation from two opposing directions. On November 14, in heavy snow, at Mirage, the scene of time and space created in the Denver Art Museum, what you heard was not congratulations, but thanks; the former is for something you have obtained, the latter is for something you have given. A star-studded night fell upon New York, wrapped up in the full range of emotions; the city lights were as brilliant as the stars themselves. Suddenly you remembered your father and the floodgates of your tears were opened…

I know that all faits accomplis are the result of movements of the universe,so there is no reason not to enjoy the glorious scenery of happiness and sorrows. I realize that there is an omnipresent rhyme and reason behind reality, and beneath it a never-resting certain trend of events. Further down is a boundless movement of energy. I hear the noise of the radio switching from one frequency to another, the echo of the cosmic Big Bang is there in that sound. I see, you are extremely tired…

You dream that the piece of writing is not yet finished…

Early hours of the morning, August 3, 2009

No. 1, A District, Heiqiao Artists Village, Cuigezhuang, Beijing. |

![]()