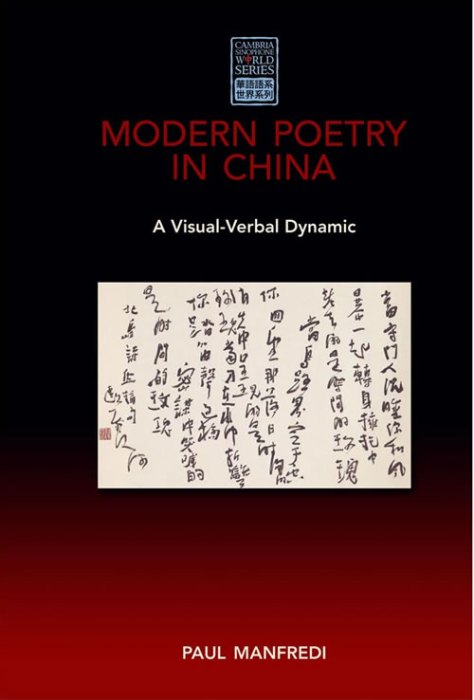

Below is an exchange of views posted to Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, a listserv managed by Kirk Denton at Ohio State University. The subject was Noble and Ignoble : Ai Weiwei: Wonderful dissident, terrible artist by Jed Perl. The original article is here

My own opinion below, and following the other posts to the list:

What has long intrigued me about Ai as provocateur, which I think is the best way to see his work either as artist or as dissident, is that he seems genuinely fearless. The clear examples are his constant challenges to Beijing (among other) authorities, whether they derive from be art-related, politically-motivated, or, more commonly, perfectly blended activities. The less obvious examples, though, are often more interesting, as with the 2010 interview with CNN (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xyAeLmN_UjA) wherein Ai proclaims (in English) that China has no philosophy, and no humanity. On that occasion I found myself wondering if he might not actually be mocking his interviewer. After all, he can’t really mean that, right?

Regardless, I was pleased with Perl’s review, mostly because I’d yet to see a single critical word about Ai in English-language press, and this fit that bill and then some. Strangely, this also provokes a somewhat defensive response from those of us in the field, myself included, who are quick to point out that Ai’s artistic work in China remains clearly more relevant than derivative. Obviously, the very idea that his work is derivative begins in an historically informed and global context, where his status (“influence”) as artist withers in the face of his heroic, even cinematic stand against the faceless regime. And of course, as Lucas observes, to get into the particulars of the dissent is more than most readers of the New York Times, Guardian, or CNN, are willing to do. But the media game is where, again, I think Ai has been concentrating his efforts since at least 2008, when the Olympics gave him direct access to a global platform. Indeed, this inclination to celebrity goes back to the days in New York, when he and many who now populate the contemporary Chinese cultural elite (image of Feng Xiaogang sitting on top of a taxi cab comes to mind) were dreaming up their somewhat impossible futures.

So my issue with Perl’s review perhaps comes down to the phrase “pleads his case in art museums.” I wonder, in fact, if that’s actually Ai pleading, or is it instead some battery of curators and art directors, who are perhaps better targets for Perl’s critique than a contemporary Chinese artist making his way, albeit willingly, in a veritable mine field of political and aesthetic explosives day after day. What Ai actually cares about is not Perl (or us), but the people who surround him, and this is perhaps the best thing that can be said about him.

The first response came from Lucas Klein.

MCLC LIST

From: Lucas Klein <[email protected]>

Subject: Ai Weiwei: wonderful dissent, terrible artist (1)

*****************************************************************

Jed Perl writes: “once upon a time Tatlin, Malevich, and El Lissitzky

imagined that they might unite radical art and radical politics.” In the

circles of American poetry I travel in, The New Republic is known to match

liberal politics with conservative aesthetics (in the same circles, those

liberal politics are often themselves seen as pretty conservative). I

haven’t paid much attention to its art criticism, but this piece by Jed

Perl (who himself is known as rather stodgy in his tastes) demonstrates

that the same may be true in visual art, too.

Here’s an example of Perl’s art historical conservatism: “If the scale of

a work and the way the work is produced are irrelevant to its meaning or

its content, then what on earth is a work of art? Isn’t a work of art by

its very nature a matter of particulars, of size and scale, of who does

what and how?” This seems like a question he might have wanted to ask Sol

Lewitt or other conceptual artists forty or fifty years ago. There’s

always the question, Would Ai Weiwei be so famous if not for his stance

against the Chinese Communist Party? But the flip-side of that is, Would

Ai Weiwei’s identity as an artist be criticized, undermined, or

second-guessed if he weren’t Chinese?

I’m not suggesting that political virtue and artistic value are the same

(I’ve posted reviews to this list specifically stating that they’re not).

But here’s how it works: Art Review magazine listed him as the most

influential person in the art world in 2011

(http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2011/10/13/ai-weiwei-on-top-of-the-art-

world/). Maybe you think he’s influential for his politics rather than for

his art, but then again, I can think of no other Chinese person who has

ever been considered most influential in the world in his or her métier

while alive; Mo Yan, Gao Xingjian, Bei Dao, Lu Xun, and Li Bai have never

been considered the most influential writers in the world, and hey,

Chairman Mao wasn’t even the most influential Communist in the world! For

some, what’s influential about Ai Weiwei’s art is that he does not want to

define his artwork only by what can be easily put on display, but rather

that his life (also on display for more reasons than one) is his artwork.

This doesn’t mean everything he does is good. I certainly don’t respond to

all his work (the appeals to the government from many mothers following

the Wenchuan earthquake, framed and hung on the wall at the Hong Kong

International Art Fair, where I saw it last May, did not move me

aesthetically, and I found his Gangnam video stupid and indulgent), but my

own take is, actually, that Ai Weiwei is a much more interesting artist

than he is a dissident. I haven’t read all his tweets or collected

writings, or even seen Never Sorry (so this is limited; please write in if

you think my judgment is hasty), but my sense is that as a political

thinker he’s a one-trick pony, saying no more or less than the Party is

bad. I have seen no systematic analysis or developed perspective, but

rather sometimes who will attack from left or right depending on what he

thinks the problem is. That’s fine, but I don’t think it makes a

compelling dissident (Liu Xiaobo, on the other hand, whom I certainly

don’t agree with all the time, has a consistent Liberal standpoint; a more

developed perspective gives him more range as a dissident). In Ai Weiwei’s

artworks, however, I see him engaging much more fully with the depth and

breadth of the Chinese cultural and political identity, and what that

means for, as John Berger put it (quoted in Perl’s piece), the “style he

inherits, the conventions he must obey, [and] his prescribed or freely

chosen subject matter.” I don’t think he can articulate his aesthetics

very well (many artists cannot), but even in the poorly lit, undersized

images of his sculptures on the New Republic webpage (as if consciously

laid out to appear diminutive), I see craft and concept combined in ways I

find not only interesting and intriguing, but beautiful.

Lucas

Following are numerous others writing to the list.

MCLC LIST

From: Stanley Seiden <[email protected]>

Subject: Ai Weiwei: wonderful dissident, terrible artist (2)

*******************************************************************

I think I disagree with both Messrs Perl and Klein. Or to speak more

positively, I agree with Perl’s assessment of Ai’s dissidence and Klein’s

with his art.

With little artistic background, I feel far less qualified to comment on

Mr. Ai’s artistic work, but as an enjoyer of art I’ve never found Ai’s

work to strike any fewer aesthetic chords in me than the oeuvre others.

The history of artwork as revisualizations of every day objects is far

older than Ai (see Duchamp’s urinal and Creed’s balls of paper). What’s

more, the mere fact of one viewer’s indifference to a piece of artwork

(such as Perl’s bafflement at Cube Light) does not diminish its impact to

others. Ai’s animal heads may be devoid of deeper meaning than a

presentation of Chinese cultural icons, but I question Perl’s seeming

renunciation of, say, the entire Pop Art movement, which was built on

nothing but stark portrayal of cultural icons. It is hard to have

patience for a critic who would allow a conversation of art without Mickey

Mouse (or 生肖鼠, I suppose).

As for the dissidence of Ai, I highly recommend watching Never Sorry for

its detailed portrayal of the shape and form of Ai’s work to criticize the

government. I say “work” because it is a laborious project. Ai doesn’t

just post the picture of his brainscan on museum walls (which both Perl

and Klein object to on different merits); he makes numerous trips to

Chengdu, files all his paperwork, and documents the entire process. The

message I took from Never Sorry, or at least from what it depicted of Ai’s

process, was that it’s never enough to simply denounce the Party as “bad.”

Ai has taken it upon himself to play out the system, follow the threads

to their end, and hold everyone (including himself) accountable for their

actions.

I think separating Ai’s artwork from his dissidence (and I don’t really

like splitting his public image into those two boxes in the first place;

there is more to Ai’s promotion of good governance in China than simply

opposition to government policy) is also somewhat self-defeating. His art

is a form of dissidence; his dissidence emerges as art. Ai Weiwei is a

man who deeply loves his country and seeks to improve the government

therein, and much of his artwork is documentation of this passion and

pursuit. Pollack threw paint against a canvas; Ai is throwing himself

against the similarly blank, expressionless expanse of the Chinese

government, in numerous shades and from numerous angles, and then leaves

us to see the marks that are left. I am a cynical art student, and I

agree with Perl that a list of names typed on paper, on its own, is

largely absent of artistic merit. But when I read that list, I am moved

by something much more potent than oils and charcoal. Ai is not going to

win a Nobel Peace Prize any time soon, but he has taught Americans (and

the world) far more about China than Liu Xiaobo or Tan Zuoren. That, too,

is a power of art: to rush in where dissidents aren’t allowed to tread.

Ai is an artist; these are his works. They have the power to stir us

emotionally, even if we don’t understand every installation. Why

shouldn’t we put them in our museums?

Stanley

============================================================

From: Kristin E Stapleton <[email protected]>

Subject: Ai Weiwei: wonderful dissident, terrible artist (3)

Dear all,

I agree with a lot of what Lucas Klein wrote in his response to the Perl

review of Ai Weiwei. Speaking without any credentials as an art critic (I

did forward the review to my colleagues in Visual Studies here in Buffalo

for their thoughts but have not heard back yet), but having seen the

Hirshhorn exhibition and the documentary, I think Ai Weiwei’s work is

trying to deal with Chinese history and the contemporary world in a

variety of interesting ways. Maybe it is the eclecticism that Perl

objects to? That light cube was not all that moving to me, either, but it

certainly immediately called to mind the total glitz attack of 1990s

Chinese commercial spaces. The map of China made out of wood reclaimed

from demolished historical buildings is pretty breathtaking, on the other

hand.

As for Ai as a “one-trick pony” political activist, I think it’s true that

in politics he is not as eclectic as in his art-making — the ability to

share ones thoughts on any subject with whomever one wants and have free

access to public information that should legally be available are what he

asks for in almost all of his “performance art.” That’s not a bad one

note for a one-trick pony to hold to, it seems to me, at this point in

history. (His broader approach to the question of the “legacy of Chinese

culture,” explored by destroying ancient artifacts, etc., is also

political, but in a broader context of cultural politics). The Gangnam

thing may be silly, but being silly is not a particular heinous offense

(at least, I certainly hope not!) and perhaps it only became publicly

known because he has decided that it’s better to just make his whole life

public than restrict it to his immediate circle and the public security

forces.

By the way, Buffalo’s Albright-Knox Gallery bought a couple of pieces from

the “Moon Chest” installation, which will come here after the exhibition

finishes its tour.

Best wishes,

Kristin

=========================================================

From: Sean Macdonald <[email protected]>

Subject: Ai Weiwei: wonderful dissident, terrible artist (4)

I read a review like Perl’s with a large grain of salt.

Different forms of contemporary art have trajectories within their

respective historical contexts. Any work or production that merits serious

consideration deserves to be criticized in the context of other works and

their institutions. Although Perl doesn’t seem to be a very nuanced art

critic, I find his comments to the originality, or lack of originality in

Ai’s work, interesting.

Perl seems to want to simply criticize Ai’s production as derivative

because Perl is anchoring Ai’s aesthetic in Western neo or contemporary

avant-garde work, work that does play with ideas of originality and mass

production. Perl has a point here. But Ai also grounds the content of his

work in contemporary PRC politics and society. Perl also seems to

understand that Ai is not the first contemporary artist to articulate

explicit political messages. Perl just doesn’t like Ai’s “messaging.”

The idea of bringing John Berger into a discussion about a contemporary

artist like Ai is also interesting, but maybe this is where Perl doesn’t

get it. For example, extrapolating from Berger, Perl claims Ai’s work

lacks “sense of the means as constituting an opportunity and a restraint.”

And what if the artist’s “lack of restraint” is precisely the point? What

if this “lack of restraint” is a kind of reply to a context (political,

social, and institutional) that still (from the point of view of the

artist) exerts too much restraint?

In the end, it is possible that neither Perl nor Ai are “conservative” or

“liberal.”

All the best,

Sean

0.000000

0.000000