Poet, critic, scholar Yang Xiaobin, now on the faculty at Academia Sinica in Taiwan, has in recent years joined the group of contemporary Chinese poets working in photography (Bei Dao, Mo Mo, Li Li among others). Yang is certainly the one whose engagement is most fully explicated in his own theoretical manner on his

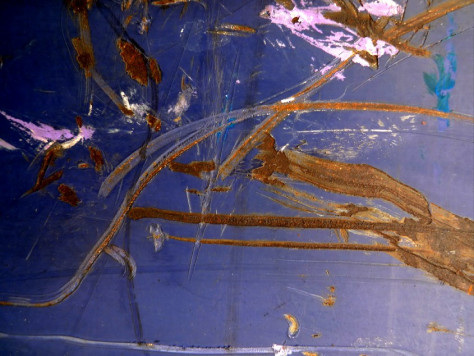

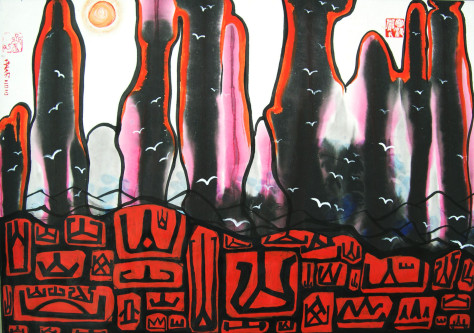

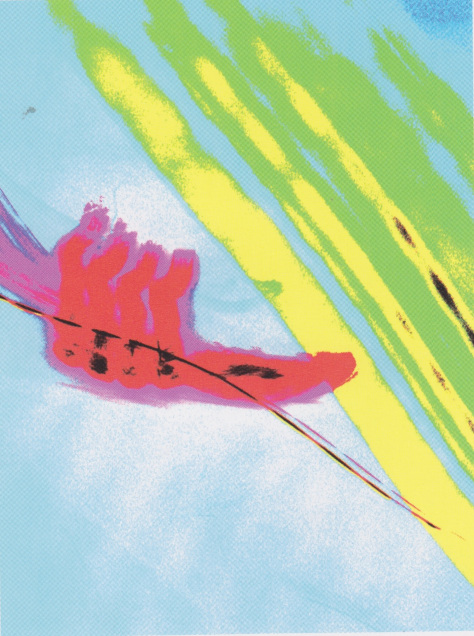

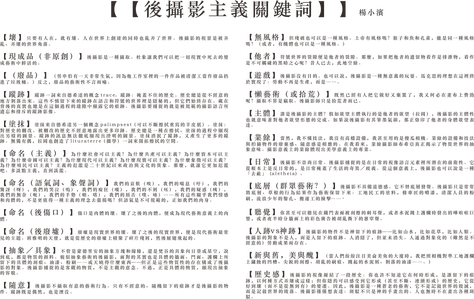

is constructed in the manner of “keywords”, including “quotidian,” “badness,” “ready-made,” “subjectivity,” “other,” “garbage,” “trace [Derrida],” “automatism,” “abstract/figural,” and so forth. His photographic images, meanwhile, were originally material objects (flat surfaces such as walls, doorways, pavement) at such acutely close-up range as to render them visually unintelligible. Since then he has moved on to something different, more tactile, and readable. Long explication of his “post-photography-ism” is Palimpsest and Trace: Post-Photographism. Sample images from the exhibition site:

More, and I think better, works available on his blog:

As for Yang’s poetry, it is often described as being difficult, or at least challenging. Here, for instance, in a translation produced by Karla Kelsey, John Gery and the poet himself, is the second of three short poems, this entitled “Bread”

BREAD

You sliced the loaf of bread with a comb,

finding inside it hairs of the dead, a squamish voice,

and dry, warmed-over love.

the bread darkened and darkened, its crumbs

more and more seared and shriveled:

Before you could wash and dress, you face, too, was burnt:

its features, not easy to swallow,

burgeon with a hunger for beauty.

面包

你用梳子切开面包。那里

有死者的发丝,娇嗔

烤热的爱。

面包越来越黑,碎屑

越来越理不清:

梳洗之前,你的脸已烧焦。

难以下咽的五官

带着美的饥饿。

*translation appears in Another Kind of Nation: An Anthology of Contemporary Chinese Poetry edited by Zhang Er and Chen Dongdong (Talisman House, 2007), 290.