Stranger Recommended

Isamu Noguchi and Qi Baishi: Beijing 1930

Tues–Sun. Through May 25. | FreeFrye Art Museum, 704 Terry Ave, 206-622-9250

Isamu Noguchi image

Now on at Frye Museum is a pair of exhibitions, one smaller, the other more ambitious, the two collectively an important because uncommonly deep meditation on artistic influence.

The first, larger exhibition is

Isamu Noguchi and Qi Baishi: Beijing 1930

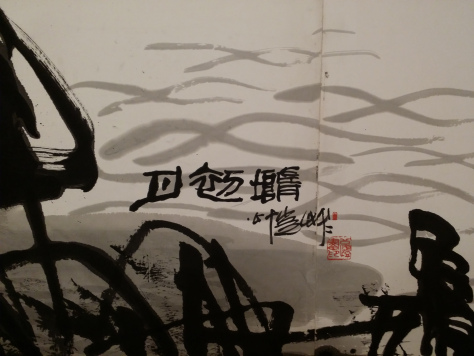

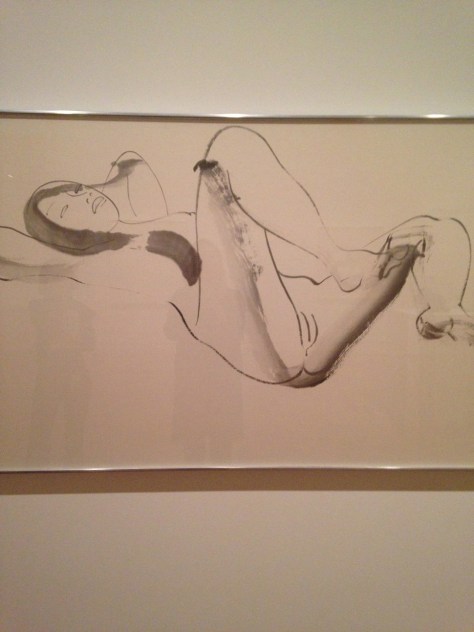

is an intimate glimpse into a ½ year-long artistic tête-à-tête which had lasting impact on Noguchi’s work in particular. Noguchi, Japanese American artist, sculptor, designer, was at the time in his late twenties when he found himself waylaid in Beijing. Making the best of his circumstances, he decided to pursue the study of ink painting with well-established artist and, in time, 20th century master Qi Baishi. The resulting images are arresting in their simplicity, particularly when paired with Qi Baishi’s paintings.

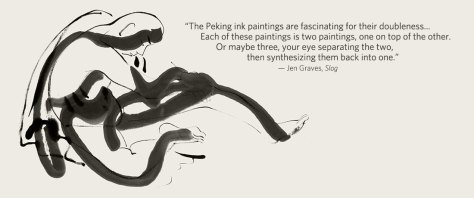

Jen Graves (side note, Seattle’s own art critic finalist for a Pulitzer award–way to go Jen!) comments on the exhibition in The Stranger with typical cogency. Among other things, she notes the one image that I’m guessing didn’t need much prompting from Qi Baishi, approaching, as Graves observes, erotica:

A striking work, to be sure.

——

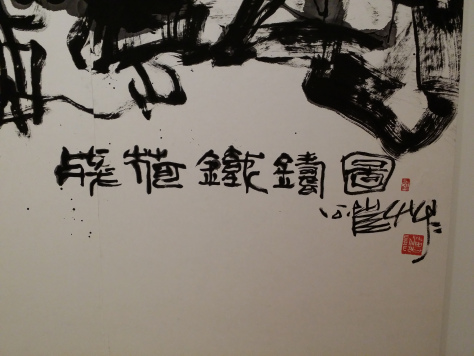

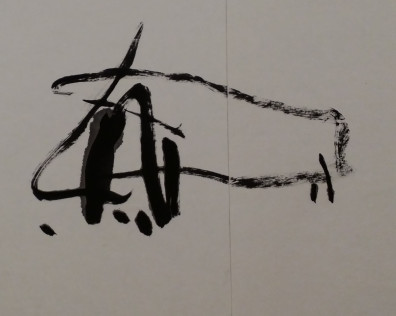

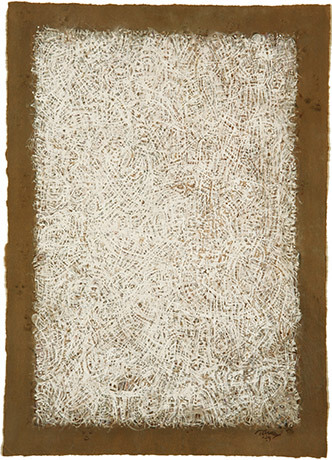

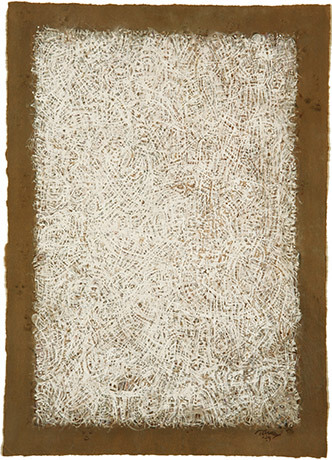

Mark Tobey, Untitled

The other exhibition,

Mark Tobey and Teng Baiye: Seattle/Shanghai

forms an important complement. Tobey’s words on traditional Chinese art: “Chinese painters, like the Futurists, don’t paint birds, they paint the flight”. The Frye description:

February 22 – May 25, 2014

Mark Tobey and Teng Baiye: Seattle/Shanghai is the first exhibition in the United States to explore artistic and intellectual exchanges between Chinese artist Teng Baiye (1900–1980) and his American contemporary Mark Tobey (1890–1976). The two first met in the 1920s, when Teng moved to Seattle to study sculpture and complete a master’s degree at the University of Washington. During this period, Tobey studied calligraphy with Teng, and the two artists formed a deep personal friendship. In 1934, Tobey visited Teng in Shanghai and soon thereafter embarked on his seminal “white writing” paintings, works considered by Western critics to be indebted to his study of calligraphy, ink painting, and the Bahá’í faith.

The present exhibitionconsiders Teng’s influence as both a cultural interpreter and an artistic practitioner on the development of Tobey’s distinctive artistic practice and—through Tobey—on the discourse on abstraction in midcentury American art. Whether Tobey’s work had remained “American” or become “oriental” was a subject of debate among contemporary observers in the United States. Merrill Rueppel, the director of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, wrote in 1968 that Tobey was “never for one moment anything but an American,” explaining that he had “taken the calligraphy of the orient and made it the foundation of his own art without becoming oriental.” Similarly, William Seitz, curator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, wrote that in Tobey’s work “the Eastern dragon had been harnessed to Western dynamism.”

In China, similar questions regarding the extent of foreign influence on the work of Teng Baiye were raised. Scholar David Clarke notes that Teng’s “sojourn in the Pacific Northwest and his sophistication in handling both Western and Chinese cultural knowledge gave him valuable resources with which to contribute to the task of assimilating lessons from elsewhere while building a national culture [in China in the 1930s].” Nevertheless, after 1949, and especially during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), Teng’s paintings were denounced as spiritual pollution. He was condemned to manual labor and few of his paintings survived.

At the time of these debates on national identity in the United States and China, Mark Tobey reflected on “the art of the future,” writing that it “cannot germinate in antagonism and national rivalry but will spring forth with a renewed growth if man in general will grow to the stature of universal citizenship.” The present exhibition provides audiences in the twenty-first century with the opportunity to consider and compare the mature work of both Teng and Tobey and to reexamine twentieth-century debates on their artistic endeavors beyond the ideological inflections and Cold War rhetoric of their day.

David Clarke, in 2011, had written on the subject, though in the case of this exhibition its pairing with the Noguchi/Qi images is particularly powerful. Certainly worth a visit.