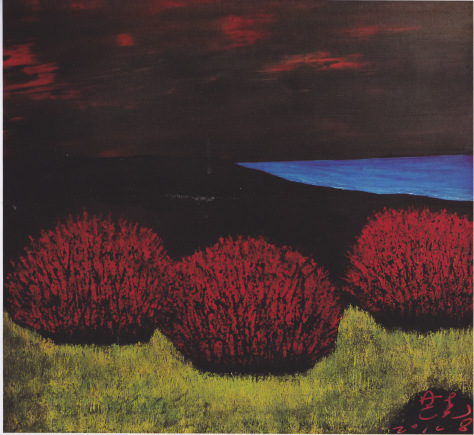

Here again working on poetry-art intersections. One interesting case in point, I think, the Chinese poet Mang Ke, one of founding members of Jintian 今天 (Today) poetry journal, and otherwise major forces in the opening up of poetic and other artistic expression in the 1970s and 1980s. Since around the year 2000, though, Mang Ke has been turning his attention more and more to oil painting, principally landscapes. For a poet towards the end of his career, particularly a career as distinguished as Mang Ke’s is, to suddenly pick up visual art is in itself an unusual event. His own explanation, in typically self-deprecatory fashion, is to suggest that he needed money to support his family, and paintings are more lucrative cultural objects than poems. Perhaps so, but one cannot detract from the rather extraordinary progress he’s made in the realm of painting in a very short space of time. Below an untitled work from 2012

Mang Ke, 2012, oil on canvas, no title, 800mm x 800mm

This I pair with “A Poem Presented to October”, here in translation by Gordon T. Osing and De-An Wu Swihart. The poem in context of painting is, to quote Octavio Paz something like translation, replete with “shadows and echoes”

1. The Crops

Quietly the Autumn fills my face;

I am the wiser.

2. Working

I want to be with the horses and carriages

pulling the sun into the wheat fields . . .

3. The Fruit

What lovely children,

what lovely eyes;

the sun himself is like a red apple,

beneath it the countless fantasies of children.

4. The Forest in Autumn

Nothing of your glance is here.

no sound of yours,

just a red scarf fallen by the way . . .

5. The Earth

All my feelings

have been baked by the sun.

6. Dawn

I wish you and I with one heart

could sweep away the darkness down the road.

7. The Sailboat

When that time comes

I will come back with the storm.

8. Sincerely Yours

I bring one rose-red petal of sunlight

and dedicate it to love.