Today courtesy of Nick Kaldis and Kirk Denton at MCLC

http://u.osu.edu/mclc/2015/10/28/dragon-in-ambush-review/

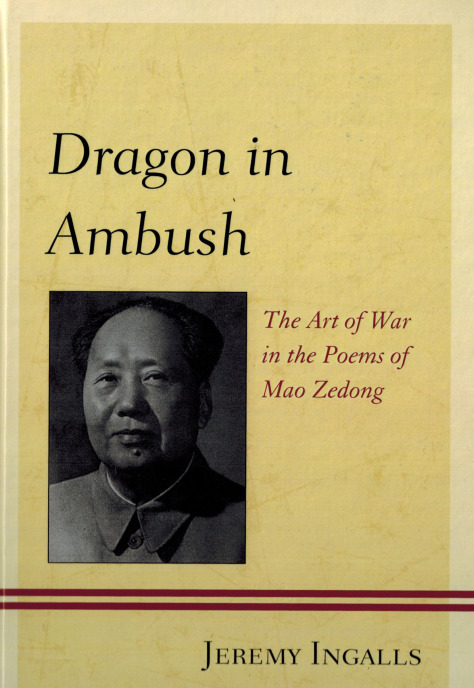

Dragon in Ambush:

The Art of War in the Poems of Mao Zedong

By Jeremy Ingalls

Reviewed by Paul Manfredi

MCLC Resource Center Publication (Copyright October, 2015)

Jeremy Ingalls (compiled and edited by Allen Wittenborn). Dragon in Ambush: The Art of War in the Poems of Mao Zedong. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2013. 420 pp. ISBN: 978-0-7391-7782-2 Hardback ($90.00 / £60.00); E-ISBN: 978-0-7391-7783-9 eBook ($89.99 / £60.00)

Jeremy Ingalls (compiled and edited by Allen Wittenborn).

Dragon in Ambush: The Art of War in the Poems of Mao Zedong

. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2013. 420 pp. ISBN: 978-0-7391-7782-2 Hardback ($90.00 / £60.00); E-ISBN: 978-0-7391-7783-9 eBook ($89.99 / £60.00)

Jeremy Ingalls’ translation and explication of Mao Zedong’s poems is an extraordinary work, so full of information that it seems bursting at its roughly 500-page seams. This is not an entirely good thing, because the information provided, while often rich and resonate, is also frequently far-fetched and the assemblage of contents is somewhat unusual. In the Preface, we are told the work is a “critique and new translation of the first twenty of Mao Zedong’s published poems” (xi). This is a deceptively simple description of what is actually a tour de force of literary scholarship, but one that veers into an odd combination of reverential reading of Mao’s poems and diatribe against Mao himself and all that he stood for.

Ingalls, for those not already familiar, was born Mildred Dodge Jeremy Ingalls in 1911 and passed away in 2000. She was a scholar, essayist, and student of Asian Languages who taught in both English and Asian Studies at University of Chicago, Western College for Women in Oxford, Ohio, and Rockford College in Illinois. Over the course of her career she was awarded the Yale Series of Young Poets Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, American Academy of Arts and Letters grant, and other awards, as well as an honorary Doctor of Literature and Letters (Litt.D.) from Tufts University in 1965, five years after her retirement. The appearance of this book in 2013 was due to the painstaking efforts of Allen Wittenborn, an associate and friend of Ingalls. Wittenborn met Ingalls at the University of Arizona, where Wittenborn was completing his graduate work in the 1970s. Wittenborn returned to the University of Arizona archives later and produced, from some fifty boxes of posthumous papers, Dragon in Ambush. Wittenborn’s presence in the manuscript is notable: large editorial notes fill out the work in important places, providing background information necessary to hold the great span of truly disparate concerns together in one work.

Structurally, the book is not particularly unusual. It is comprised of two major sections, with Part 1 “Recognizing the Terrain” (a little over one hundred pages) divided into two chapters—”Methods of Approach” and “A Rationale for Ruthlessness”—and Part 2 “Mao’s Poems 1-20” (nearly 300 pages) comprising the translations, with poems appearing in pinyin, traditional and simplified characters, and English. Why, precisely, it was necessary to include both traditional and simplified characters is a bit of a mystery, and the pinyin also seems overkill, but the work is consistently thorough, and these elements are in keeping with that trait. The commentary that follows each poem, meanwhile, is truly exhaustive, working through line by line with general historical setting for twenty of Mao’s poems composed between 1925 and 1936, full explication of textual origins wherein demonstration of Ingalls’ extensive knowledge of classical Chinese literature is in full display, and a smattering of notes on translation issues, particularly as they relate to potential cultural miscommunication. In the translation discussion we can see that Ingalls takes her readership to be those generally interested in Mao’s work but with little knowledge of Chinese literature, recent or ancient.

The really curious part of the work is its intent. Ingalls seems less inclined to educate readers about Mao’s poetic writing than to make them acutely aware of the way Mao’s dastardly plans for world domination are manifest in his poetical writing. In Ingalls’ estimation, the poetry can be read first as a chronicle of Mao’s political thinking of the time, but also as a grand plan for the future for those learned enough to “read between the lines” (3). Ingalls observes:

Acquaintance with what these poems are asserting and proposing is crucial for those of us who recognize the continuing costs to humanity of seemingly effective despotisms and the aggravation of those costs by eloquence dedicated to the celebration of massively artful control over the destinies of other human beings. (ibid)

Two points about this bear immediate mention. First, that poetry could be used in such a way—to cleverly communicate a momentous scheme to a group of would-be political followers—is in itself fascinating. Ingalls’ view is that Mao the poet writes work that is consistently bifurcated, simultaneously communicating on one level with the masses and offering on another an esoteric layer of often conflicting information to be comprehended only by the truly worthy. The second point, perhaps less of a novelty in Mao studies generally but still fresh in the context of literary studies of Mao, is that the textual origins of Mao’s lyrical personae lie almost entirely outside of Marxist-Leninism. They are instead a collection of classical Chinese texts including principally Sun Zi’s Art of War, the Book of Changes, and Laozi’s Dao De Jing. The crux of Ingalls’ work is the identification of a stratum of readers, of which she is the preeminent example, who can actually unravel the dense allusions at work Mao’s poetry, revealing at last what Mao intended his poetry to actually do for his contemporaries and future generations. As readers, or “explorers” as Ingalls names us, we are initiated by her into an even deeper cognoscenti status than the one signaled by the texts themselves, aware of Mao’s hidden agenda and those to whom the agenda is addressed.

Ingalls builds the case for Mao’s nefariousness in the second chapter, appropriately titled: “A Rationale for Ruthlessness.” She opens with a discussion of the thirty two instances of the use of tian 天 in Mao’s twenty poems. Here, though, we immediately see a strange combination of scholarly, well-researched material and willfully unusual readings of Chinese classical texts. Chapter V of the Dao De Jing, for instance, begins with the lines: 天地不仁 / 以萬物為芻狗 / 聖人不仁 / 以百姓為芻狗. Ingalls renders these: “Heaven, in dealing with Earth, is ruthless / Using the ten thousand phenomena as straw dogs / The sage, in dealing with humankind, is ruthless / Using all of the people as straw dogs” (41) [italics mine]. This is not to say that her translation is wrong per se, but it is not standard. Though “ruthless” is a reasonable choice, the phrase is actually “not ren,” where ren (benevolent) is a fundamentally human psychological or moral attitude that is not a part of the nature signified by the phrase “Heaven and Earth,” to which it is here predicated. Further, by breaking the first two characters “Heaven and Earth” 天地 into: “Heaven, in dealing with Earth,” she sets up an oppositional force that is odd at best. Regrettably, this is an essential feature of Ingalls’ view of Mao’s appropriation of traditional literature; she believes Mao aligns himself with Heaven in opposition to Earth. Thus, the distance between ruler and ruled recapitulates Heaven’s ruthless “dealing” with Earth. In other words, Mao treats all people as “straw dogs,” only useful in their function of allowing him to achieve his principal goal of total domination. Ingalls writes:

In this rationale, the inherent ruthlessness and the inherent duration predicted, in analogy with Heaven, of the sage as a cosmically validated commander of humankind, supply the premises of Mao’s poems 5 and 21. In these poems he speaks of the ageless energy that he believes he possesses, in common with Heaven, in exercising, like Heaven, a ruthless activation of the process of change. (43)

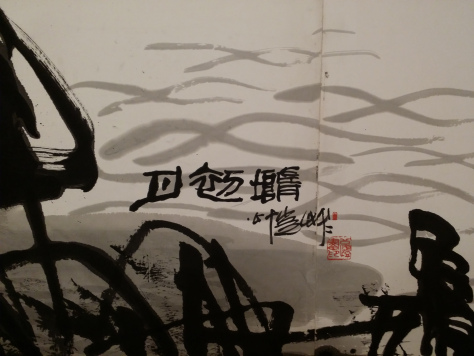

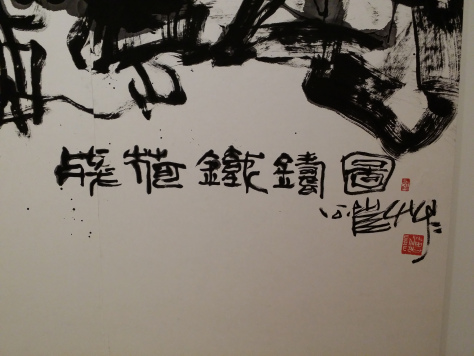

The readings of the poems demonstrate similar orientation, often leading to interpretations that strain credibility. Poem 17, “Long March” (长征), might strike most readers as a celebration of Red Army exploits at a historical moment when success of the communists was anything but a foregone conclusion. Here is the original poem in full:

紅軍不怕遠征難,

萬水千山隻等閑。

五嶺逶迤騰細浪,

烏蒙磅礡走泥丸。

金沙水拍雲崖暖,

大渡橋橫鐵索寒。

更喜岷山千裡雪,

三軍過后盡開顏。

As is well known, Mao’s troops were outnumbered by and materially disadvantaged in comparison with the Nationalists. Mao’s poem describes the ease with which the Red Army travel difficult terrain, defiantly smiling as it reaches its goal. In Ingalls reading, though, these lines become something very different. Poem 17, she describes in her commentary, is

marked by a sustained ambiguity as to whose thoughts the poem is expressing. . . . Mao’s phrasing of his poem . . . sets up the suggestion that the thoughts might be those of the Red Armies but indicates, to close readers, that he is, by intention, summarizing, instead, his appraisal of the usefulness of the expedition to his personal political advantage. (292)

And a short time later:

A Mao Zedong who, like some of his predecessors, including the putative Zhou authors of the Zhou text of the Changes, considers himself endowed with unique talents and obligations to impose a “correct” government upon the human race can, without compunction, regard tens of thousands of human beings as expendable as long as, through this process, he grooms survivors docilely obedient to his further commands. (295)

What Ingalls sees as patently sinister in Mao’s work has its origins in Chinese political philosophy, a flawed system perhaps, but also perhaps no more necessarily conducive to world domination than any other. The essential problem with Ingalls’ work, which seems almost too obvious to observe, is that the “world” of Sun Zi, Lao Zi and the Zhou authors was not that of the 1920s and 1930s when Mao was writing, and thus the charge that Mao intended world domination based on his poetic appropriations of those texts is a bit absurd. Equally absurd is that the albeit over-confident and brazen lyrical persona of Mao’s poetic writing would actually have an intended result—if indeed such was Mao’s intent—to sway populations outside of Mao’s actual control. Ingalls again:

It is, therefore, scarcely surprising that Mao should suppose that, having proved himself an even more ruthlessly successful manipulator of human beings and human affairs than Zhuge Liang, the impact of the career of Mao Zedong and of his words . . . will enforce Mao’s dragon-claw grip upon the shaping of human events through many centuries to come. (99)

For anyone interested in Mao’s poems, or even in Mao himself, this book is immensely useful. As Wittenborn observes in the Preface, one cannot glean a full picture of the man without careful reading of the poems, because what Mao presents in his prose writings is for an entirely different audience. The argument that only in the poems does Mao’s true nature reveal itself, a position that might serve as a sort of raison d’être for the work as a whole, is convincing in a way. However, as Ingalls’ prevailing psychological characterization of Mao is that of a ruthless leader unconcerned with the people he purports to lead, the potential value of reading the poetry is greatly diminished. In fact, with Mao’s careful, even masterful, attention to poetic diction and other detailed elements of the texts, a truly astute reading, the like of which Ingalls advocates, could yield far more than a picture of mere ruthlessness at work in Mao’s poems. Unfortunately, for all of her efforts, Ingalls herself seems to be unable to grasp this broader view.

One final point is worth contemplating. From the wary or even alarmist tone of Ingalls writing one might suppose that she was engaged in analysis of the poetical writings of a living world leader, one who could, conceivably, extend his merciless revolutionary influence to lands outside of China. Given the rather restricted nature of information available outside China during the Cultural Revolution in particular, this might account for Ingalls’ concern about a world leader bent on something far more than governing just China. Obviously, limitations resulting from a lack of credible information of what was happening inside China during the Cultural Revolution and shortly thereafter, when Ingalls presumably began work on the project, could easily have been rectified in the years following Mao’s death with some judicious editing and revision. The incubation of Ingalls’ notes was decades long, certainly enough time to accomplish this task. Nonetheless, with the considerable volume of source material created in the 1970s, the sense that the Mao dragon was much more than poetic fantasy makes a degree of sense in the context of that time.

Whatever one’s political position, historical and/or literary training, Ingalls book is a rich source of information about Mao’s poetic work, and in some respects his personal and political philosophy. It is not challenging to sift through the dense commentary—which demonstrates at times an overabundant antipathy for Mao’s political project and slightly hysterical response to his hegemonic intentions—to find insights about his poetical work, particularly as regards his connection to classical Chinese literature. For those who have a low tolerance for narrow ideological reading, though, such a sifting process might be more onerous than it is worth.

Paul Manfredi ([email protected])

Pacific Lutheran University